The Scandalous Story Behind M&Ms’ Name

When the business of candy isn’t so sweet.

You’ve seen “Willy Wonka,” right? If so, you’ll remember not only the candy factory’s unpredictable impresario but also his nemesis — the sneaky, spying Slugworth. You may have wondered, is the world of candy manufacturing really that cutthroat?

Actually, it’s worse. There might not be a real Wonka, but there was a real Slugworth, and his name was Forrest Mars.

Forrest was the son of Frank C. Mars, the founder of Mars Incorporated. As a small child with polio, Frank learned to dip chocolate from his mother, and when he became an adult he spun that talent into a thriving business. When he died in 1934, that business passed on to Forrest.

Father and son weren’t on the best of terms when the two were alive, though. Forrest rarely saw his dad after his parents divorced, and instead of being given a position in the company, he was sent overseas and told to start his own business.

When he returned to the fold, he was ready to upend his Dad’s legacy and make Mars into the dominant force in American candy. Forrest brought a pathological obsession with quality control to Mars. When he spotted a mis-wrapped candy bar in a store, he furiously returned to the production plant and spent an afternoon throwing product against a glass window in front of horrified executives. Even now, Mars disposes of millions of M&Ms every day because they aren’t up to standards. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves here.

Let’s meet the other player in our tale: Bruce Murrie. Also a second-generation candy man, Bruce was the son of William Murrie, the president of Hershey’s from 1908 to 1947. Like Forrest Mars, Bruce didn’t agree with how his father was running the company. Hershey had long been risk-averse, content with pumping out Kisses and bars without innovating. Bruce wanted to push the medium of candy forward, so he went looking outside of Hershey for an unlikely partner.

During the Spanish Civil War, Forrest Mars had seen soldiers eating an unusual chocolate candy of pill-sized nuggets encased in a hard panned sugar shell. More portable than a standard candy bar and heat-resistant in an era before mass refrigeration, they were just waiting to meet the American market.

But Mars needed access to more chocolate to do it. And Hershey had it, because they weren’t subject to rationing. So Bruce made a deal to supply Mars with the resources to make the new candy in exchange for 20% of the partnership. The two men called their new company “Mars & Murrie.”

M&M for short.

After production began, M&M cut a deal to sell them exclusively to the US Armed Forces so soldiers could have sweets in their rations no matter where they were in the world. By the time GIs returned home, they were addicted to them. By 1956, they were the country’s best-selling candy.

None of that mattered to Bruce Murrie, though. Forrest Mars leveraged him out of his 20% share in 1949 and became the only M in M&M. Forrest was a terror to work with, upbraiding Bruce Murrie at every turn. He would personally blame Bruce for low sales and publicly humiliate him in front of the employees, and after a few years Bruce had had enough.

Forrest paid a paltry $1 million for Bruce’s share of a business that was doing a billion dollars in sales a year. He then folded M&M back into the main Mars corporate umbrella.

Unfortunately for Bruce Murrie, his extracurricular activities had made him persona non grata at Hershey, who weren’t happy about Mars’ growing market share. Even with his father as a former President, Bruce couldn’t get back in the door. Giving Mars a leg up in the industry was seen as an unforgivable act of treason. As Forrest’s company thrived, Bruce Murrie was never heard from again.

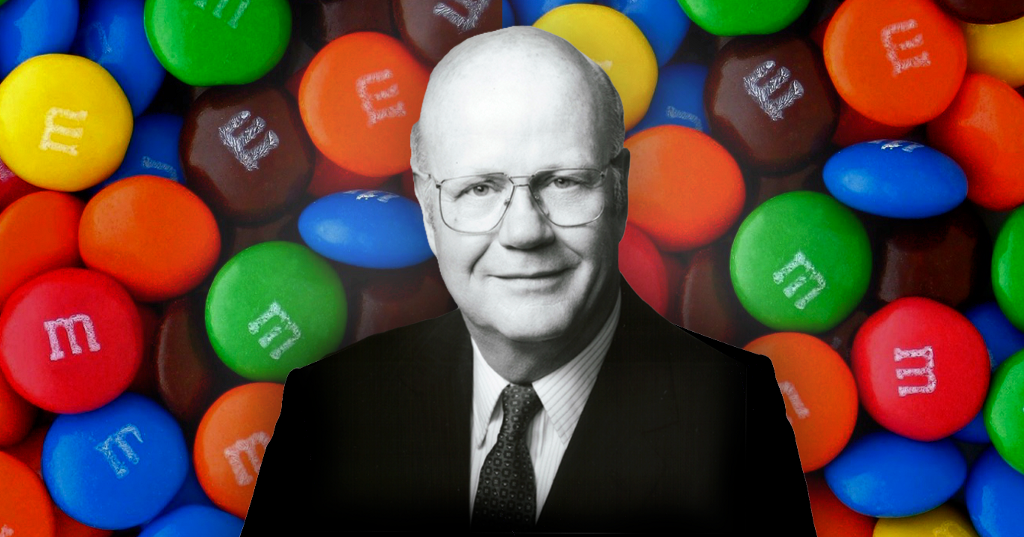

Forrest Mars retired in 1973, passing the business on to his children. To this day, the Mars family — and the Mars company — still marches to the beat of his drum. All employees sign oaths of secrecy, nobody has their own office, and the company carries no debt. Rumor has it the Mars heirs are forbidden from ever selling any portion of their ownership in the company. Mars now produces 400 million M&Ms each and every day, each one bearing the initial of the man who made them possible, or the man who ruined his life.