Meet The Man Catching Serial Killers With Data

Forget guns or handcuffs. Thomas Hargrove is armed with an algorithm.

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight.

Thomas Hargrove knew there was a serial killer in Gary, Indiana before the police did. In fact, he told them in 2010, but never got a response. Five years later, police charged Darren Deon Vann with the murder of seven women in and around Gary. During Vann’s arrest, he casually mentioned that he’d been killing people since the 1990s.

So how did Hargrove, a 61-year-old retired reporter in Virginia, know something the police department didn’t?

Data.

Hargrove is the founder of the Murder Accountability Project (MAP), a non-profit organization that collects crime data from federal, state and local governments via public reports and Freedom of Information Act requests. MAP uses that data to build the most complete database of homicide information available to the public online, completely free.

MAP brings awareness to under-reported and unsolved homicides in the US, but its real claim to fame is Hargrove’s serial killer algorithm.

Hargrove, who was the subject of a fascinating profile in Bloomberg Businessweek recently, told the magazine that his interest in the power of data began in college. As a student, he took an interest in political polling data, which served as a useful skill when he was a reporter in Washington DC after graduating. While working on a story about prostitution in 2004, Hargrove sourced his data from the most comprehensive database he could access, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report. This report includes all criminal activity reported to the FBI in a given year.

Attached to the Uniform Crime Report was a Supplementary Homicide Report which breaks down murder statistics by the victim’s age, race and sex, method and location of killing and any details about the offender.

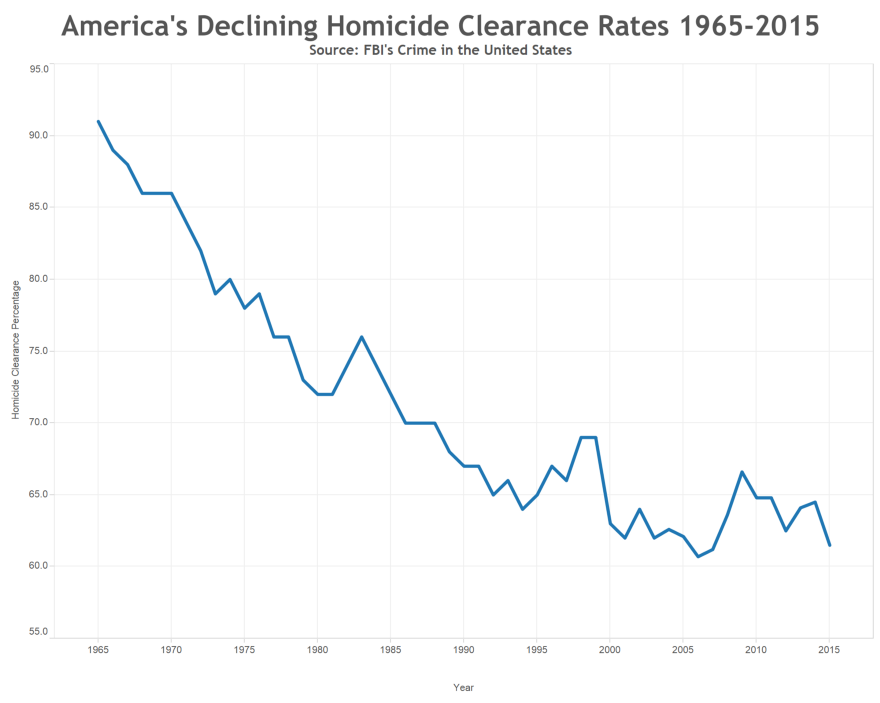

As Hargrove reviewed the available FBI homicide data, he was struck by the clearance rate — a homicide investigation is “cleared” when law enforcement arrests a suspect. National clearance rates are abysmal, with only 58% cleared in 2015, according to the MAP’s database. The rate used to be much higher: in 1965, it was 91%.

Hargrove’s analytical mind lit up as he scanned rows and rows of the report. He tells Bloomberg, “The second I saw that thing, I asked myself, ‘Do you suppose it’s possible to teach a computer how to spot serial killers?’”

The Murder Algorithm

In 2008, four years after Hargrove first learned about the Uniform Crime Report, he entered the homicide data from the 2008 report into statistical software. Then he went about developing an algorithm to pick out crimes that might have the same killer. After countless ideations, he settled on a “cluster analysis,” compiling a victim’s geography, sex, age and their method of killing to represent the most important aspects of the crime.

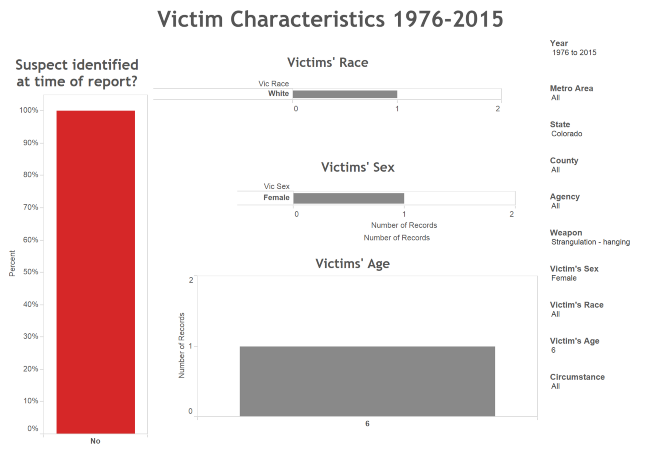

The program then compares the clusters to pick out potential victims of the same killer. When Hargrove presents his program as a resource for homicide investigators, he uses the case of JonBenét Ramsey, the child beauty pageant star killed in her family’s home in 1996. When Hargrove sets “Colorado” as location, “female” as sex, “6” as age, and “strangulation” as method of killing, the program only finds one result: JonBenét. But by broadening the age range to “5–10,” it picks up another unsolved case of a 10-year-old girl found strangled in 1985. When he searches nationwide, the program finds 22 unsolved cases that match the cluster.

Police work is notoriously low-tech. While compiling homicide statistics, Hargrove found that many police jurisdictions not only ignore the valuable FBI resource, they don’t contribute their own data to the FBI’s database, either.

Fighting Crime With Data

Hargrove has presented the MAP database and cluster analysis algorithm to homicide detectives at the FBI’s Training Division in Quantico, Virginia and at meetings of the International Homicide Investigators Association, a global training organization for law enforcement professionals. He’s had great reception after the presentations, but getting people to act is harder.

However, many cities who have prioritized raising clearing rates have shown that concerted efforts can be successful. Michael Nutter ran for mayor of Philadelphia in 2007 with a campaign focus of solving major crimes. With Nutter as mayor, the Philadelphia clearance rate rose from 56% to 75% in two years. In 10 years, the Santa Ana clearance rate rocketed to nearly 100% after a new police chief created special homicide units and revamped the reward system for tips leading to arrests.

Other cities have also utilized data technology to revamp their policing process. The LA Police Department uses historical data to predict where crimes are likely to occur and stations officers nearby to prevent crime and speed up response times. Their efforts resulted in a 13% crime reduction after 4 months of implementation.

Crowdsourcing Homicide Investigation

Unfortunately, many jurisdictions lack the funding to devote resources to backlogged homicide investigations, let alone data collection and analysis. Homicide investigations are funded with tax dollars and when there’s less money, the police force feels the consequences. “When an economy fails enough and we just have to start firing cops, we see everything going to hell,” Hargrove tells Bloomberg.

This is where the algorithm shines. Investigators, police departments and even concerned citizens can become researchers since the database is accessible to everyone. After Vann’s arrest and confession, Hargrove used it to work with the police department in Austin, Texas (where Vann used to live) to determine if Vann might be the killer in any of the city’s unsolved cases.

There’s a constant worry that robots will render humans obsolete, but in this case Hargrove and his algorithm fill a void most people aren’t even aware of. That’s another of MAP’s goals — to give everyone easy access to unsolved homicide cases. This provides people the opportunity to contact lawmakers and police departments to voice their concerns and create a crowdsourcing resource for investigation.

“You can call up your hometown and look and see if you see anything suspicious,” Hargrove explains. “If you’re the father of a murdered daughter, you can call up her record, and you can see if there might be other records that match.”

And with at least 5,000 killers in the US getting away with murder every year, it’s about time we take help from everyone and every algorithm we can.