The Undercover Journalist Who Exposed Abuse At An Insane Asylum

Nellie Bly wanted society to embrace the mentally ill, not push them into a corner.

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight.

In 2012, Ryan Murphy released the second season of his TV series, “American Horror Story.” The story is set in a fictional mental asylum, but Murphy and his team pulled from real life events to underscore the narrative’s spookiness: Dr. Arthur Arden (aka Hans Gruper) is based on notorious and sadistic Auschwitz physician Josef Mengele; the sociopathic Dr. Oliver Thredson is modeled after infamous murderer Ed Gein.

Most notably, Sarah Paulson’s character — a journalist who infiltrates Briarcliff Manor to get the scoop on the institution — is based on a young, investigative journalist who went by the alias Nellie Bly.

Tumultuous beginnings

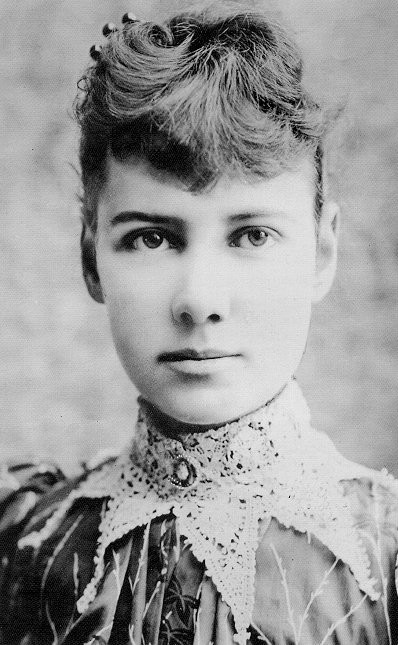

Nellie Bly was born Elizabeth Jane Cochran in 1864 in Cochran’s Mills, Pennsylvania. Her early life was privileged. The town was named after her father, an esteemed judge and businessman. He married twice and had 15 children between his two wives (Elizabeth was number 13). He died when she was six, and neglected to recognize his second family in his will. In an effort to make ends meet, the family worked odd jobs and supported themselves by opening a boarding house in Pittsburgh.

This time proved especially challenging for Elizabeth, who suffered abuse at the hands of her new stepfather and yearned to escape.

At 15, she trained to become a teacher, but soon ran out of money to continue her education. Her story might have ended there if it wasn’t for an anonymous letter she wrote to the editor of the Pittsburgh Dispatch, responding to a column that railed against the idea of women working. The editor was so impressed by Elizabeth’s writing that he offered her a job as a reporter. She was only 21 at the time.

An investigative pioneer

Elizabeth soon took on the alias Nellie Bly. Her work centered on women’s rights and misogyny. A pioneer in the field of investigative journalism, she would dive deep into her research, assuming disguises to expose unsafe labor practices in female-operated sweatshops. In spite of her obvious passion and talent for reporting, the paper relegated Nellie to fluff stories and women’s issues. When it became apparent that the Dispatch would not allow her to write the articles she wanted to write, she left.

Nellie moved to New York and found work with the publisher New York World. The paper commissioned Nellie to investigate Blackwell’s Island Asylum — an institution for insane women. In 1887 at the age of 23, Nellie agreed to pose as a mentally ill person in order to gain entry into the asylum and investigate undercover. To do so, she posed as Nellie Brown, an immigrant from Cuba, and made a scene in a women’s dormitory. After fooling several doctors, first at court and subsequently at Bellevue, Nellie infiltrated Blackwell.

Ten days in a madhouse

Purchased by the city of New York in 1832, Blackwell Island was built as a haven for people unable to assimilate into society. The island measured two miles wide and, after funding was cut, housed 1,600 residents in cells designed to accommodate a population of 800.

Once Nellie was committed to the asylum and transferred to the island, she realized how terrible the conditions were. Patients endured ice baths, freezing cold temperatures and inedible foods; the staff would beat and starve the occupants and subject them to unsafe and unhygienic conditions. Sick patients grew sicker and sane patients were prohibited from leaving.

Nellie quickly realized the asylum was unsuitable for humans, but she had disguised herself too well — even after she revealed her sanity, the hospital’s staff maintained she was crazy and would not grant her leave. Nellie initially intended to be placed in a violent ward, but after hearing firsthand accounts of the beatings and mistreatment endured by those patients, she decided against it.

Nellie remained in Blackwell for ten days, at which point the paper dispatched an attorney to free her. Upon her release, she published an article headlined “Ten Days In A Madhouse.” The article caused such a stir that Nellie was called upon to testify in front of a grand jury about the experiences she and her fellow patients endured. Subsequently, the asylum terminated key members of the staff and made steps towards improving the institution’s food and sanitation. Most importantly, Nellie’s story caused the committee of appropriations to set aside an additional $1,000,000 to help benefit the insane.

A life well lived

If Nellie Bly had chosen to do nothing else with her life, her contributions towards improving life for the mentally ill would have been enough. Her story helped lessen the stigma around mental health and took steps towards creating a climate in which legislators and community-members saw the mentally ill as people to be helped, rather than problems to be shunted away and hidden.

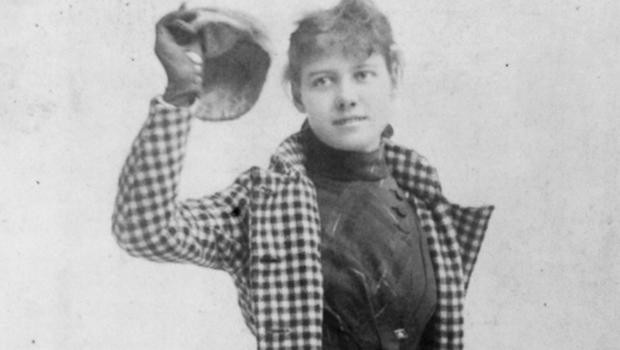

After her adventure in Blackwell, Nellie continued writing, infusing humanity into stories about the Pullman worker strikes in Chicago and profiling famous political activists like Susan B. Anthony and Emma Goldman. Her celebrity profile increased in 1889 when she circumnavigated the globe in 72 days, challenging the record set by protagonist Phileas Fogg in the novel, “Around the World in 80 Days.”

In 1895, 30-year-old Nellie married Robert Seaman, an oil tycoon 40 years her senior. After he died, she took over his company. Nellie Bly died from pneumonia in 1923 at the age of 57. Her life was short, but her impact is still felt today — especially by people who struggle with mental wellness.