That ‘Guilty’ Look On Your Dog’s Face Isn’t Guilt At All

What it REALLY is will make you feel worse.

My dog tells on himself. I know he’s done something wrong when I find him sitting at the end of the hallway. Normally, Waylon — my Old English Sheepdog — approaches me with the enthusiasm of an out-of-town grandmother, but when trouble is afoot, he lowers his head toward the ground and looks up at me, showing the whites of his eyes. “Where is it?” I hiss.

While I search for a mangled remote or pick up garbage from the floor, shouting, “BAD DOG,” Waylon retreats to the bathroom. I pull him out to wave the evidence in front of his nose, booming his least favorite words: “WHAT IS THIS?”

Waylon lowers his chin and pins his ears back apologetically. I sense his remorse and my heart melts.

But is he really regretful? According to dog cognition scientist Dr. Alexandra Horowitz, my dog isn’t experiencing a lick of guilt. Instead, he’s feeling a more basic emotion: fear.

Horowitz’s 2009 study explores the human tendency to assign human emotions to dogs, a species that processes thought differently.

When my dodo dog’s eyes disappear into his face and his tongue nips the air, my human brain analyzes the traits and misattributes them to guilt — a complex, human form of fear.

The study found that dogs’ expressions of guilt were actually reactions to their fear of being scolded, rather than appreciating a misdeed.

“It seems unlikely that they have the same types of thinking about thinking that we do, because of their really different brains, but in most ways dogs’ brains are more similar to ours than dissimilar,” Dr. Horowitz tells Business Insider.

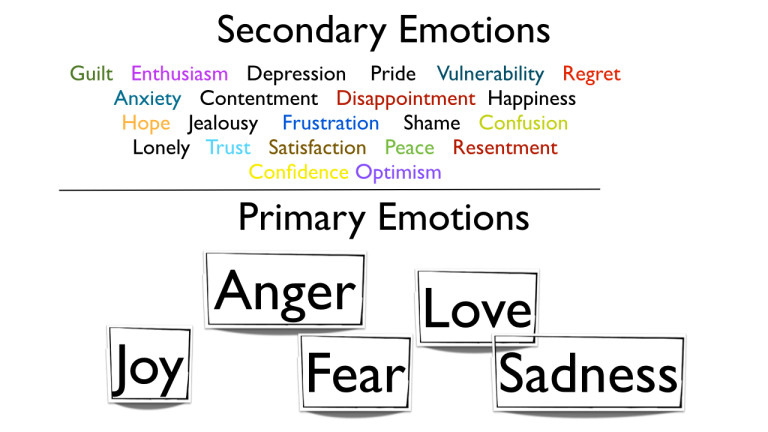

Whether or not dogs experience guilt is hard to say. Fear — along with anger, sadness and joy — is a primary emotion. In an article in Psychology Today, psychiatrist and philosopher Neel Burton, M.D. describes primary emotions as “‘cognitively impenetrable,’ that is, unconscious and uncontrollable, and more akin to a reaction than a deliberate action.”

In contrast, guilt is a secondary emotion, a more complex chain of thinking which requires reflection — or, thinking about thinking. Burton suggests thinking of primary emotions as building blocks, with secondary emotions being more “complex blends” of a primary.

According to Horowitz, there is no evidence that suggests dogs reflect on past actions to determine if they’ve done something wrong.

“There is some work showing that some animals are planning for the future and remember specific episodes in the past,” Horowitz says. “With dogs, there’s not as much evidence yet. Which isn’t to say that they don’t, but it’s to say that it’s really hard to design experiments around it.”

The harrowing part of Horowitz’s findings, of course, is that my actions cause my dog to feel afraid. I recall my nasty behavior towards him and reflect. And you know what? It makes me feel guilty.