How Stoned College Kids Invented Modern Anesthesia

It’s all fun and games until someone cuts a tumor off your neck.

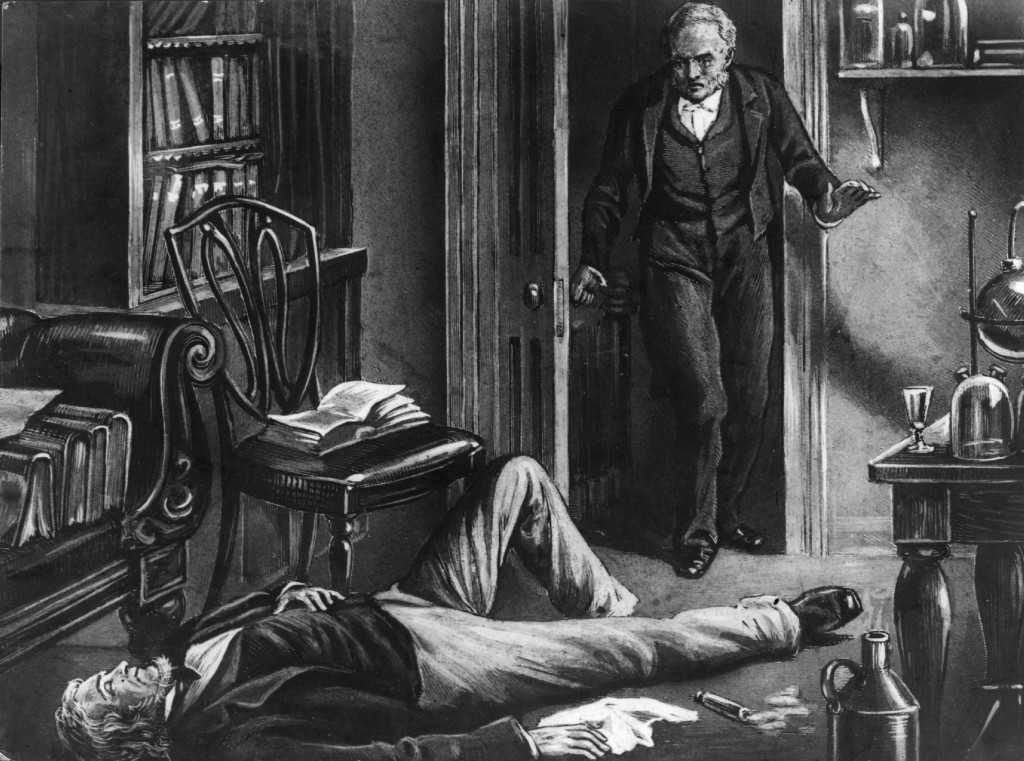

Imagine being strapped to an operating table, wide awake while a surgeon cuts off your leg with a saw. Until 175 years ago, that’s what having surgery was like.

Since the time of the Greek doctor Hippocrates (460 BC), Western surgeons had tried doping surgical patients with opiates, cannabis, alcohol and a variety of plant-based poisons. They “bled” them until they passed out. No matter which method was used, subjects woke, screaming, when the cutting began. Some died from the pain and shock.

Surgery was considered a last resort because of what Dr. E.M. Magruder calls the “agony of the knife” in a 1917 historical essay in the International Journal of Surgery. “The interior of hospitals was made hideous with the cries and groans of surgical victims,” he writes.

The irony is that by the 1800s, there were known drugs — ether, nitrous oxide and chloroform — that could have been used as anesthetics. Doctors just weren’t using them.

One of the first to discover a potential anesthesia was British dentist Sir Humphrey Davey. In 1799, Davey discovered that gaseous nitrous oxide could cure a toothache. Tantalizingly, he even wrote that “it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations.” But doctors considered nitrous oxide a “poison,” and none tried using it as an anesthesia.

Doctors knew about another “poison” called sulphuric ether. They considered the colorless, odorless liquid a potential asthma treatment. None tried it as an anesthesia — but lots of people took it for fun. While drinking or inhaling enough ether makes you unconscious, smaller doses make you high. I mean really high.

“It makes you behave like the village drunkard in some early Irish novel,” Hunter S. Thompson writes in his 1971 “gonzo” journalist work “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.” Quoting from experience, Thompson says ether causes a “total loss of all basic motor skills: Blurred vision, no balance, numb tongue-severance of all connection between the body and the brain. Which is interesting, because the brain continues to function more or less normally … you can actually watch yourself behaving in this terrible way, but you can’t control it.”

“There is nothing in the world more helpless and irresponsible and depraved than a man in the depths of an ether binge,” Thompson concludes.

Ether was really popular in Europe in the first half of the 19th century. For example, Irish people drank it to get around the Catholic church’s prohibition of alcohol. It was even sold in pubs — right alongside beer and whisky.

As Magruder writes, ether was also popularized by an “odd class of persons” who traveled between Britain and the US, lecturing the public on chemistry. These lecturers customarily asked volunteers from the audience to come up on stage and inhale ether (or nitrous) “for the purpose of provoking exhilaration, excitement, semiconscious gyrations and other mirth-provoking antics for the amusement of spectators.” These events were called “ether frolics.” They were also popular at private homes and in medical colleges.

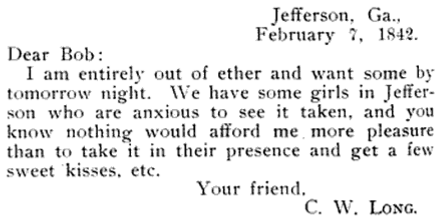

Much as college students hold drug parties today, Crawford W. Long of Jefferson, Georgia indulged in “ether frolics” while attending University of Pennsylvania medical school in the late 1830s. He held them in his room, and when he moved back to Georgia to start his medical practice, he held ether parties at his house.

After one such frolic around Christmas 1842, Long noticed bruises on his body, from injuries he hadn’t remembered sustaining. He later watched as etherized friends sustained blows or falls that should have been really painful — one suffered a debilitating ankle injury — without feeling a thing. Long concluded that ether might be a good anesthetic. (Perhaps understandably, he couldn’t remember the exact date he came to this conclusion.)

One of Long’s patients, James Venable, had two tumors on his neck, but was afraid to undergo surgery for fear of the pain. But Venable did like going to “ether frolics.”

So on March 30, 1842, Long proposed excising the tumor, while Venable inhaled vapor from an ether-soaked towel. Venable agreed. When the surgery was over, Venable didn’t believe it had even taken place, until Long showed him the excised tumor.

Long had made the “grandest discovery of the universe,” writes Magruder, “by the side of which Columbus’ discovery of America, Newton’s discovery of the law of gravitation, Watt’s discovery of the expansive force of steam, and Fulton’s invention of the steamboat, are compelled to take second place.”

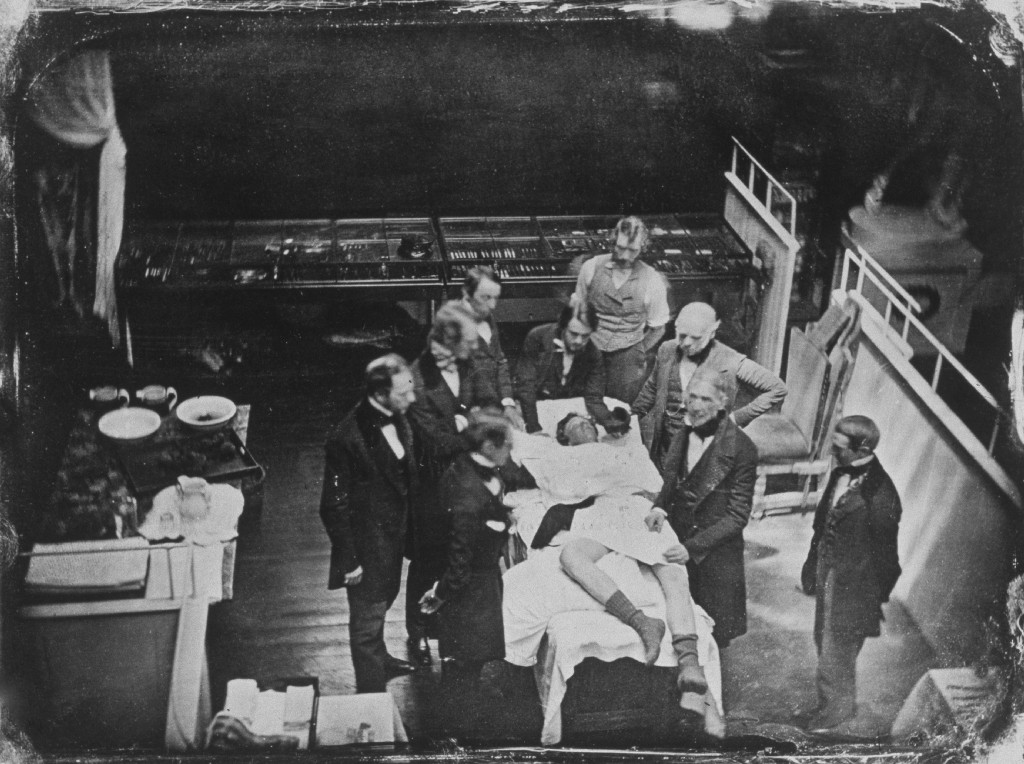

In the next few years other doctors made the connection between party gases and anesthesia. In 1844, Dentist Dr. Horace Wells attended a wandering lecturer’s “nitrous frolic.” Wells asked the lecturer to dose him with nitrous while a fellow dentist pulled his tooth — painlessly. Dr. Thomas Morton went to an “ether frolic” in 1846, and then used ether to painlessly extract a patient’s tooth.

Long published his research in 1849, and ether and similar drugs became standard in operating theaters. After more than a thousand years of excruciating suffering, surgery went from a last resort to something patients actually asked for, to end their suffering quickly and painlessly. And for that, we can all thank medical students and their drug parties.