The White Reporter Who Pretended To Be Black During Jim Crow

‘Most Southern blacks didn’t hate whites, but saw them as fellow victims in a system beyond their control.’

James R. Crawford had only been on the segregated train headed south for a few hours when he started disliking white people.

He resented their “impudent assumption that [he] wanted to mingle with them” and “their arrogant and conceited pretense that … each and every one of them, was of a superior breed.”

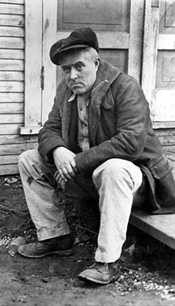

The thing was, Crawford was white too. His name was actually Ray Sprigle. He was a reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette newspaper and had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1938 for exposing a Supreme Court judge as a Ku Klux Klan member.

Sprigle was no bleeding heart. He was a staunch conservative; he’d fiercely opposed FDR’s New Deal. However, he believed Jim Crow “grossly oppressed blacks” and wanted to experience for himself what that oppression was like. So in 1948, he headed South — disguised as a black person.

After staining his skin with walnut juice and a series of chemicals hadn’t worked (and hurt a lot) Sprigle chose a simpler route: He got a tan in Florida, shaved his head, and donned the flat cap many Southern black men wore at the time.

Sprigle had a friend at the NAACP who hooked him up with a guide: John Wesley Dobbs, a prominent black leader in Atlanta. Sprigle’s contact at the NAACP hadn’t told Dobbs that Sprigle was actually a white guy in disguise, so Dobbs thought Sprigle was James R. Crawford, a black Mason from Pittsburgh who was headed south to learn political organizing techniques from Southern civil-rights activists.

Dobbs gave Sprigle the rundown on being black in the South. Don’t use bus seats, restaurants, water fountains or bathrooms reserved for whites, he told him. Don’t bump into a white man or even brush past a white woman. And if a white man attacks you, don’t resist — or you’ll get lynched.

As Sprigle and Dobbs walked from the colored coach to the colored dining area, Sprigle was already “beginning to think like a black man.” In his 21-part series for the Post-Gazette, he wrote: “I quit being white, and free, and an American citizen when I climbed aboard that Jim Crow coach.”

The two men traveled almost 4,000 miles by car and by train through Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee over the course of four weeks. Sprigle soon realized that his “concern over acquiring a dark skin” was “so much nonsense.” Everywhere he went, he encountered black people with skin as white as his.

In the countless black homes, churches and community meetings the pair visited, virtually no one suspected Sprigle wasn’t “just what I pretended to be, a light-skinned Negro from Pittsburgh, down South on a visit.” They just told him their stories, which graphically illustrated “the one great facet of these people’s lives — their relations with the whites.”

In his journalism, Sprigle described some of the appalling racism he witnessed in the South. In Georgia, the hundreds of miles of coastline were whites-only. Blacks who tried to swim were jailed and fined. A black sharecropper earned $700 a year for harvesting crops worth $5,400 to the white plantation owner. And he was one of the lucky ones. Macy Yost Snipes was a black soldier who’d returned to Georgia a hero from WWII, only to be shot dead on his lawn for being the first black person in his county to vote. His attackers claimed self-defense, though Yost was unarmed. The bigots later ran his family out of the state.

In the Mississippi Delta, plantation owners were above the law. Sprigle called it the “last outpost of feudalism in America.” In a particularly horrifying story he overheard, Sprigle said a white foreman, “gun-hung like a one-man army,” rode up to a black undertaker. “In the friendliest tone imaginable he called out: ‘Jim, I just had to kill that brother of your down near his place [sic]. Better see to getting his body out of there’ — and galloped off again.”

White men killed black men for imagined slights — or sometimes just to test out a new gun. If a black man resisted an attack by a white man, the black man would try his best to kill him outright. If you’re going to be killed, black men told Sprigle, better give the white folks something good to kill you for.

Sprigle’s newspaper series recounted all of this in stark, graphic detail. He directly equated “Southern values” with white supremacy. He was surprised to learn that most Southern blacks didn’t hate whites, but saw them as fellow victims in a system beyond their control. If given another couple of months as a black man, Sprigle predicted, “I’m pretty sure I’d be hating the whole damned white race.”

The series was syndicated and ran in papers nationwide — except the South. Civil rights issues were starting to gain attention, and Sprigle got hundreds of letters — 70% of them were negative, the Post-Gazette noted. White-owned Southern papers penned rebuttals, culminating in a debate between Sprigle and a prominent Mississippi editor that was televised live nationwide.

Sprigle died in 1957, less than 10 years after his trip to the South. His journey had forever changed him: “To tell the truth, I doubt if I ever regain the satisfied, superior white psychology that I took South with me.” His activist traveling companion Dobbs died in 1961, on the same day Atlanta desegregated its schools. A statue in a park there memorializes him. Sprigle is immortalized in his words alone.