Britain’s First Female Doctor Posed As A Man

She performed the first recorded C-section.

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight.

The pistol weighed heavily in the Irish doctor’s hand, an instrument of death unlike the scalpels and saws he was used to handling. As the sun rose over the Cape Town estate, Dr. James Barry squinted at his opponent 20 paces away. The handkerchief fluttered — the signal to fire!—and two pistols cracked.

How had it come to this? Hot-tempered James had insulted Captain Cloete, his rival for the paternal affections of the governor of the South African colony. A furious Cloete retaliated by tweaking (yes, tweaking) the doctor’s nose. Traditions of Irish honor were clear: The only way to settle the matter was a duel.

Cloete reeled as the bullet struck his peaked hat. James felt a sharp pain in his thigh. As the surgeon attending the duel moved forward with scissors to cut off James’ pant leg, the injured doctor stopped him. He’d dress the wound himself. The esteemed Dr. James Barry could not let his secret be discovered: He was actually a woman!

Margaret Ann Bulkley was born in 1789 in Cork, Ireland. History tells us she was likely a tomboy who dreamed of being a soldier, and once asked her father for a uniform and a sword. When she was 6, her older brother John bankrupted the family by paying to marry a wealthy woman he’d fallen in love with.

Margaret went to live with her uncle in London. His society friends admired the girl’s intelligence and began tutoring her. One of them, a Venezuelan general and revolutionary, told Margaret she should pose as a man to enter medical school, then join his rebellion against Spain, working openly as a female doctor in Venezuela.

Thus “James Barry” entered Edinburgh medical school in 1809. “He” was actually 20 but claimed to be 14 because he looked so young. Three years later, as James was secretly about to become the first woman to receive an MD, Spain put down the Venezuelan revolt and imprisoned the general. So James enlisted in the British Army. Historians believe his uncle’s friend, Lord Buchan, helped him enlist without submitting to a physical.

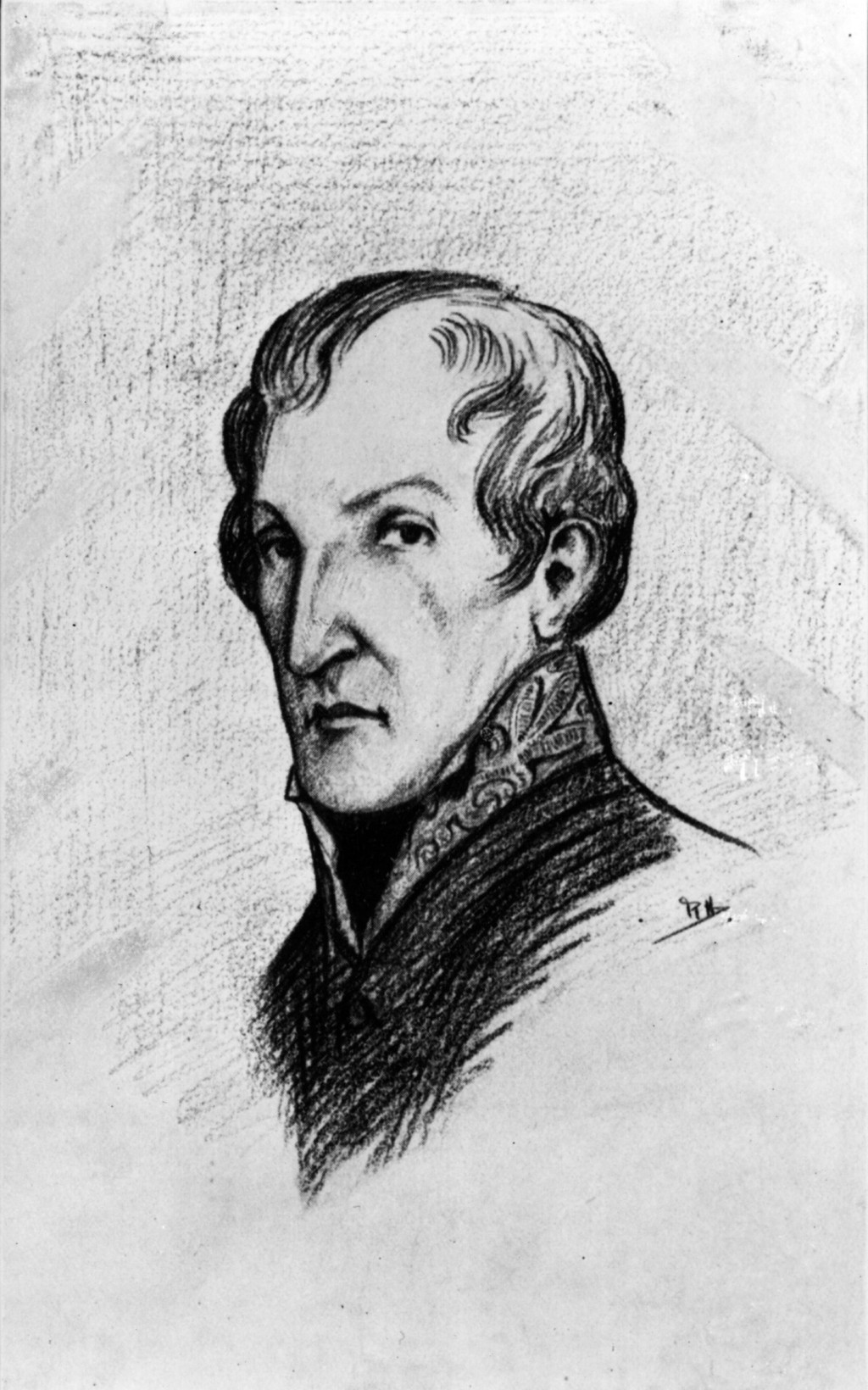

Already considered a prodigy due to his apparent youth, James was named assistant surgeon of the Cape of Good Hope colony in South Africa in 1816. James decked himself in an officer’s uniform, complete with sword and spurs. Three-inch heels brought his height to just over five feet. He commissioned a palm-sized portrait of himself (below left), as young officers often did.

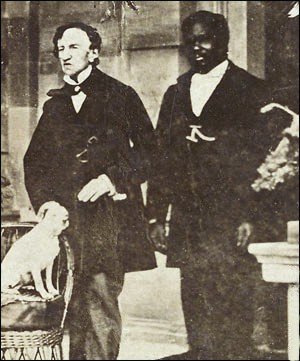

Upon arriving in Cape Town, James’ first act was to treat the sick daughter of the governor, Lord Charles Somerset. When the doctor cured her, Lord Charles virtually adopted James into his family. (There were later rumors that the two were a gay couple.)

Each day, his black servant Danzer — who would serve James for 50 years — laid out 6 towels which he used to hide his curves and broaden his shoulders.

People still gossiped. Patient William Dillon wrote, “From the awkwardness of his gait and the shape of his person, it was the prevailing opinion that he was a female.” Historians Michael Dupreez and Jeremy Dronfield disagree, arguing that most people “simply wouldn’t credit” that a woman could be a doctor.

Perhaps to allay suspicion, James cursed like a sailor. He “was a flirt…He had a winning way with women,” acquaintances wrote, noting he was “a perfect dancer who won his way to many a heart” — sometimes to the chagrin of husbands.

James gained a foul-tempered reputation, perhaps because he was ginger and Irish, or perhaps because keeping a secret strained him. One officer wrote, “There was a certain effeminacy in his manner, which he seemed to be always striving to overcome.” James fought a second duel after his standoff with Cloete, and once when an officer exclaimed, “By the Powers, you look more like a woman than a man!” James lashed a bullwhip across his face.

He was known as an tyrannical doctor. When seeing a new patient, he dispensed with all previous treatments and often, in a “frenzy of rage,” berated other practitioners. “He behaved like a brute,” wrote pioneering nurse Florence Nightengale of James, calling him “the most hardened creature I ever met throughout the army.”

His bedside manner was normally far gentler. One patient said, “It might have been a woman touching my head; the doctor’s hands are so light” and indeed, his “beautiful small white hands were the envy of many a lady.”

James performed the first recorded Caesarean section of a pregnant woman in 1826, perhaps because he had insight male doctors did not. He gave the grateful patient his tiny portrait as a keepsake.

When Lord Charles fell violently ill, James tended him until he died in 1831. Of him, James wrote, he was “my more than father, my almost only friend.”

James went on to serve in Europe, India, the Caribbean and Canada, eventually becoming Inspector General, one of the army’s top medical posts. He created strict new hygiene standards, an improved diet for patients and new medicines for syphilis and gonorrhea. He worked diligently to improve the welfare of commoners and slaves wherever he encountered them.

James took ill in Canada in 1856 and returned to England, where he died in 1865, possibly of dysentery. His last wish was that his clothes not be removed. But someone — Dupreez and Dronfield think it was a female undertaker — disrobed the corpse and reported what she found. The army was furious at the deception and feared a scandal. They published no obituary and suppressed James’ records for 100 years — suppressing his contributions to medicine right along with them. The scandal broke, anyway. Charles Dickens documented it in “A Mystery Still.”

Scholar Isobel Rae discovered Barry’s papers in 1958 and published “The Strange Story of Dr James Barry.” A century after his death, the pioneering doctor’s many accomplishments were finally before the public eye. Rachel Weisz is set to play him in the film based on his life.