This Openly Gay Activist Was MLK’s Right-Hand Man

But you’ve never heard of him.

Bayard Rustin was one of the chief strategists behind the civil rights movement, but you’ve probably never heard his name. Often referred to as the “unknown hero” of the movement, Bayard led an advocacy career that spanned over five decades and ended only with his death.

Bayard Rustin was born on March 17, 1912 in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Raised by his grandparents, Bayard grew up believing that his mother was his older sister. The Rustin family was heavily involved in the civil rights movement: Bayard’s grandmother was a member of the NAACP and activists like W.E.B. Du Bois and James Weldon were frequent guests at the Rustin home.

Bayard’s early exposure to activism influenced the rest of his life. In 1932, he enrolled at Wilberforce University, a historically black university in Ohio. Shortly before he was slated to graduate, the administration expelled him after he organized a strike protesting the poor quality of the school’s cafeteria offerings.

In 1936, Bayard moved to New York City to study at New York City College. Here he campaigned to free the nine black teenagers — the Scottsboro Boys — who were falsely accused of raping two white women on a train. That same year, Bayard joined the Communist Party, but left five years later to become a socialist.

Civil rights activism

In 1941, Bayard met socialist and civil rights leader, Philip Randolph. The two men joined forces to help plan the 1941 March on Washington to protest racial discrimination within the military. The march was later cancelled after President Roosevelt agreed to open up thousands of armed forces jobs to black Americans.

Prior to working as a civil rights leader, Bayard worked with the Free India Movement, fighting to secure the country’s independence from Great Britain. Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent tactics made a strong impression on Bayard and he later advised MLK Jr. and other civil rights leaders to adapt a similar strategy.

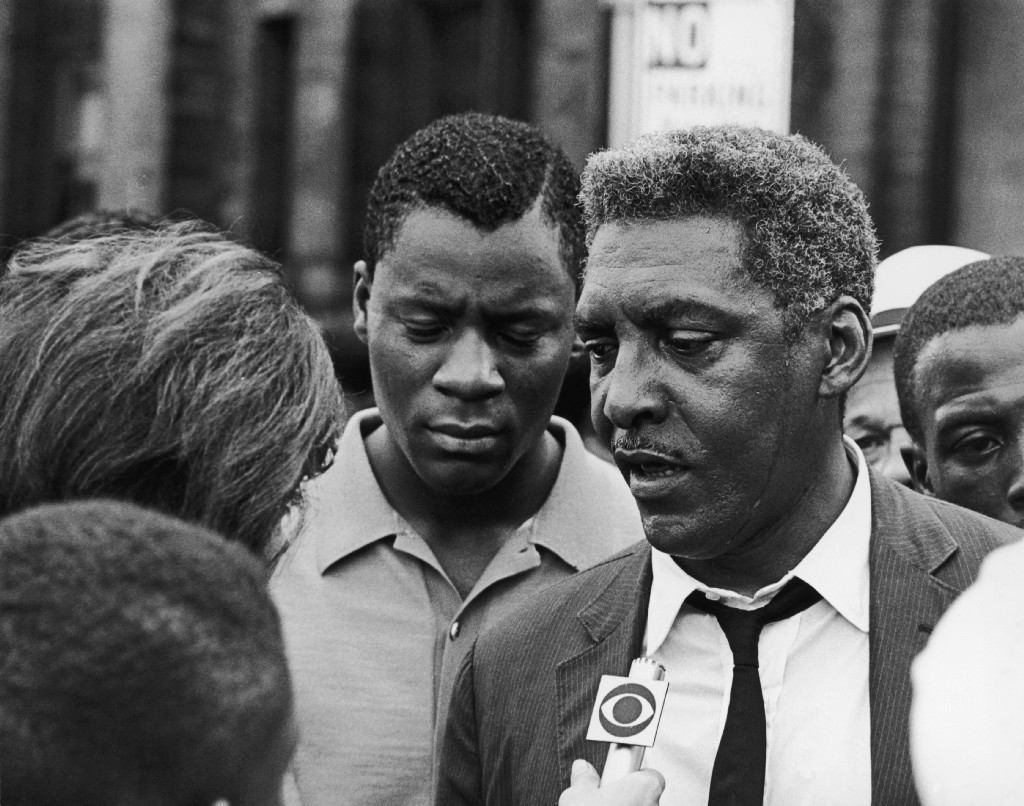

In 1963, Bayard helped organize another march: the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He is credited with architecting the entire protest, which gathered over 200,000 men and women on the National Mall in Washington. It was here, on August 28th, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

Even after the success of the march, Bayard continued to push for integration and acceptance. In 1964, he organized a one-day boycott of New York City schools, protesting the city’s board of education. On February 3rd, 1964, more than 464,000 school children remained home.

Bayard helped pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He served as a mentor for young activist groups like Congress on Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He worked to support initiatives overseas, too, helping garner American support for South Africa’s peaceful transition to democracy. As a missionary, Bayard helped refugees from countries like Haiti and Vietnam.

Gay rights activism

Bayard Rustin once said, “No group is ultimately safe from prejudice, bigotry and harassment so long as any group is subject to special negative treatment.” His words still ring true today, especially for those marginalized by movements like feminism, which often struggles to create a climate of intersectionality.

Bayard Rustin’s achievements are exemplary, but the reason you’ve never heard of him is largely on purpose. Despite his talent and reputation as an intellectual and brilliant tactician, Bayard lived life as an openly gay man during a time when homosexuals were still easy targets for marginalization and discrimination.

Referred to as a “sex pervert” by both political opponents and allies, Bayard recognized that his sexuality might detract from his value as a leader. Consequently, he preferred to work behind the scenes, so as not to provide any further ammunition for his political detractors.

Bayard was imprisoned over 20 times during his career, including a 28-month stint for refusing to serve in the military during World War II. In 1953, Bayard was arrested for homosexual activity; this was only one of many personal attacks he suffered for refusing to live in the closet.

Like all same-sex couples of their generation, Bayard and his boyfriend, Walter Naegle, were denied the rights and protections afforded to married couples. To circumvent this inequity, Bayard adopted Walter in the 1980s. Later, many other gay couples employed this same tactic, especially those looking to protect loved ones during the height of the AIDS epidemic.

Bayard continued to demand equal protections for LGBTQ folk throughout the course of his life. He advocated for New York legislation protecting queer citizens against discrimination in the areas of housing, employment and public accommodations. After a 15-year struggle, lawmakers passed legislation to that effect in 1986.

Bayard Rustin passed away a year later, at the age of 75. He died on August 24, 1987 from cardiac arrest. In 2013, President Obama granted him a posthumous Presidential Medal of Honor, recognizing his commitment to civil and gay rights activism. Walter Naegle accepted the award on his behalf.

Bayard Rustin spent his entire life in pursuit of equality and justice for all. He lived openly and worked to make America a safer and more welcoming place for all marginalized people. His legacy is best summarized by his own words:

“Let us be enraged about injustice, but let us not be destroyed by it.”