This Website Will Tell You If You’re Descended From Witches

Find out if your ancestors practiced magic.

At some point in life (usually childhood), most of us have asked ourselves: Could I be a witch? My questioning moment came after watching Hermione Granger master “Wingardium Leviosa,” which I replicated with my toy wand, convinced I had (very) slightly raised a feather off the ground.

It’s easy to imagine wanting to be a witch when pop culture gives us characters like Hermione, the Sanderson Sisters, and Willow Rosenberg—all powerful figures who cast magical spells to get what they want.

But in reality, witchcraft has a very dark history—even beyond Salem. Scotland, for instance, reached peak terror in the late 1650s/early 1660s, with witchcraft scares and trials inciting fear across the country. Scotland played host to some of Europe’s most brutal mass witch trials and prosecutions, with most of the accused tortured into confessing.

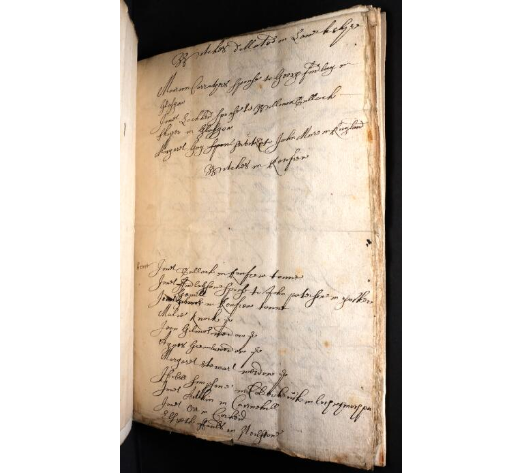

If you’re of Scottish descent, there’s now a way to find out if your ancestors were among the accused. London’s Wellcome Library digitized a 350-year-old manuscript consisting of the names of Scottish men and women blamed for practicing witchcraft between 1658 and 1662. According to a press release, the book also contains the people’s town names and notes about their “confessions.”

It’s estimated that between 3,000 to 5,000 people in Scotland were publicly accused of witchcraft during the 16th and 17th centuries. After the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 made witchcraft a crime punishable by death, revolts and trials began getting out of control. At least 2,000 people were killed before the Act was repealed in 1736, according to Smithsonian Mag.

The manuscript logs the identities of the accused. Jon Gilchreist and Robert Semple from Dumbarton, for instance, are recorded as sailors. James Lerile of Alloway, Ayr, is ominously written to be “clenged” or “cleaned”; however, that likely means his fate was death. The majority of the accused are women.

“This manuscript offers us a glimpse into a world that often went undocumented,” Dr. Christopher Hilton, Senior Archivist at Wellcome Library, said in a press release. “How ordinary people, outside the mainstream of science and medicine, tried to bring order and control to the world around them. This might mean charms and spells, or the use of healing herbs and other types of folk medicine, or both. We’ll probably never know the combinations of events that saw each of these individuals accused of witchcraft.”

We may not know exactly what happened, but the ledger stands as a fascinating—if macabre—souvenir of a time when folklore and the occult held formidable sway over the lives of ordinary citizens.