Was History’s Most Brutal Murderer Really So Bad?

When Vlad the Impaler wasn’t impaling, he actually got sh*t done.

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight.

Okay, you don’t get nicknamed “The Impaler” by being a softie, and Prince Vlad III was no softie. But how did he become one of the most reviled figures in history? Sure, he liked to impale — a LOT — but Genghis Khan killed millions, yet he’s seen as a force of creative destruction who remade the world, while poor Vlad’s just viewed as a monster. Let’s take a look at what we know.

Vlad was the son of the ferociously-named Vlad Dracul (“The Dragon”), prince of the country of Walachia, in what is now southern Romania, in 1431. Vlad III inherited the name Draculea, or “Son of the Dragon,” and even signed documents with it. He would be dubbed “The Impaler” by foreign chroniclers after his death.

English author Bram Stoker named the monster in his 1897 horror novel “Dracula” after Vlad, and placed Dracula’s castle in neighboring Transylvania. But it’s not known whether Stoker knew anything about Vlad’s history. He may have just liked the name and the setting.

“When Stoker wrote ‘Dracula,’ the Romanian countryside was considered atmospheric, mysterious, even spooky. What a perfect place to set a vampire story!”

—Arie Kaplan, “Dracula: The Life of Vlad the Impaler”

In the 1400s, tiny Walachia was uncomfortably sandwiched between two great powers. The Hungarian Kingdom lay to the north. To the south, much of the Balkans had been conquered by the mighty Ottoman Turkish empire. To survive, Walachia constantly made and broke alliances with greater powers. In one such reversal in 1442, Vlad Dracul agreed to become a vassal of the Ottomans. The sultan demanded Vlad’s sons Vlad III and Radu be sent to him as hostages, to ensure the bargain would be kept.

Walachia was internally unstable, too. Instead of the princedom passing from father to eldest son, noble families chose the next prince. This system ensured that subterfuge and violence were the routes to the throne. Vlad Dracul was assassinated in 1447, and the younger Vlad returned home a year later. He won his father’s seat, but was deposed two months later. In the next 30 years, until Vlad’s death, the throne would change hands six more times. The longest of Vlad’s three reigns would last from 1456 to 1462. They would be tumultuous years.

The capital of the Christian East Roman Empire, Constantinople, had fallen to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Massive Islamic armies suddenly threatened all of Christian Europe. The Hungarian Kingdom declared itself the defender of Christendom.

Tiny Walachia was on the front line.

Though Walachia would fall to the Ottomans after his death, Vlad fought the Turks aggressively. It’s this period that inspired the horror stories. He invaded the Ottoman lands himself, writing that he had slaughtered over “23,884 Turks and Bulgarians” during his campaign. When the sultan invaded Walachia, Vlad prepared a horrifying welcome — using his own people. A Greek historian, writing at the time, described the scene:

“And there were large stakes on which they could see the impaled bodies of men, women, and children, about twenty thousand of them, as they said; quite a spectacle for the Turks and the Sultan himself! The Sultan, in wonder, kept saying that he could not conquer the country of a man who could do such terrible and unnatural things, and put his power and his subjects to such use.” — Laonikos Chalkokondyles, “The Histories”

Another widely-repeated tale claims two messengers who came before Vlad refused to remove their hats, so Vlad nailed them to their heads. (Though in some stories, they’re Italians wearing berets. In others, they’re Turkish men with turbans.)

Turkish accounts, naturally, must be taken with a grain of salt. They tend to play up Vlad’s cruelty while downplaying his strategic acumen.

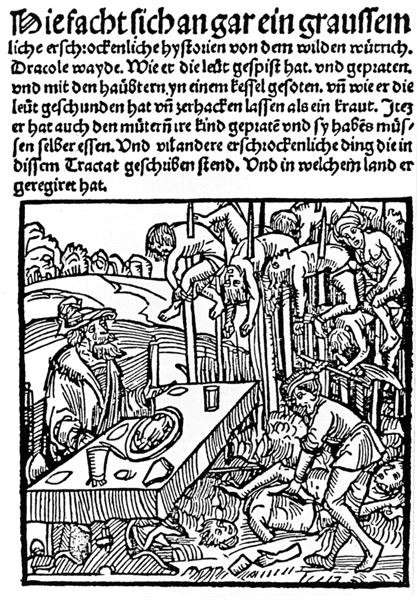

The accounts most responsible for spreading the story of Vlad throughout Europe were German — tracts published by Saxon merchants who had a stranglehold on trade in neighboring Transylvania. They were supporting rival claimants to Vlad’s throne and Vlad was determined to stamp them out. The most damaging tract was printed in Nuremberg after Vlad’s death, and describes the penalty he inflicted after the Saxons had repeatedly refused to pay him taxes. It was this tract that dubbed Vlad “The Impaler.”

“He impaled people and roasted them and boiled their heads in a kettle and skinned people and hacked them to pieces like cabbage. He also roasted the children of mothers and they had to eat the children themselves. And many other horrible things are written in this tract and in the land he ruled.”

—Nuremberg Tract, 1499

Other accounts come to us from Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus, who had a complex relationship with the politically-weaker prince. While Vlad eventually married one of the king’s daughters, Corvinus also imprisoned him for a time, after he came seeking aid to fight the Ottomans.

“Matei Cazacu (a historian at the Sorbonne), argued quite convincingly that Vlad was the first victim of printed political propaganda initiated by Matthias Corvinus and that he…was a small piece in a very big political and economic game.”

—Elizabeth Miller, Report of the World Dracula Congress

By contrast, most Russian accounts treated Vlad favorably. So did Romanian oral histories that have been passed down through the centuries. To them, Vlad’s brutal executions of criminals makes him a sort of law-and-order man, even a pious one.

“Dracula so hated evil in his land that if someone stole, lied or committed some injustice, he was not likely to stay alive. Whether he was a nobleman, or a priest or a monk or a common man, and even if he had great wealth, he could not escape death if he were dishonest.”

—Russian account quoted in “In Search of Dracula”

Many accounts, in fact, showcase Vlad’s piety. A few years after he killed his political adversary Vladislav II, Vlad built a monastery on the site of the murder. He built other religious structures, some of which are still being discovered today, and gave “land and privileges” to monasteries and abbeys.

Over the centuries, many of the sensational and potentially spurious chronicles of Vlad’s violence faded from public memory. But that all changed in 1972, when Raymond T. McNally and Radu R. Florescu published “In Search of Dracula.” The book recounted the tales of Vlad’s most violent acts for modern readers for the first time, reignited historical interest and became a bestseller.

New York Times reviewer George Stade criticized the authors for calling their own historical accuracy into doubt, with “a number of cute rhetorical questions, such as ‘Are there mysteries here beyond the reach of historical research?’”

Worse — if you’re Romanian, anyway — the book also asserted that Stoker’s novel was based on Vlad III’s life. Historians debate that assertion, but Romanian scholar Nicolae Paduraru told the Los Angeles Times that the book had “badly maimed” Romanian history, permanently muddying the waters by equating a purely fictional monster with a real historical personage.

After the fall of Communism, Bram Stoker’s novel was republished in Romania in 1993, to coincide with the release of “Dracula” by Francis Ford Coppola, a film that blended the stories of the monster and the prince together. Ordinary Romanians were horrified, not by the tale of the bloodsucking monster, but the discovery that their legendary national hero, who had helped build the country and defend it from Ottoman control for many years, had been written off, by much of the world, as a monster himself.

Romanian scholars and tourism companies launched a campaign to clear Vlad’s name. A symposium, the World Dracula Congress, was convened in 1995 (it’s now annual) and tours were organized. Tourists were as likely to hear a lecture on history as they were anything relating to vampires.

Several Romanian scholars have also published histories of their own, dispelling myths and attempting to create a clearer picture of the prince.

For example, experts note that impaling was a common execution method in Vlad’s day—though the prince certainly gained notoriety via the sheer numbers of people he impaled.

And what of Dracula’s famous castle? While Bran Castle sits imposingly astride the border between Walachia and Transylvania, and is universally associated with the legendary vampire, there’s no evidence Bram Stoker ever knew about it.