Why The French Still Hunt Werewolves Today

‘Twilight’ doesn’t do justice to this beast’s badass backstory.

As Halloween approaches, many of us will dress up as suave Transylvanian vampires or sexy English pirates. But if you really want to affect that sophisticated European air, you should go as a werewolf. Don’t believe me? Ask the French! Turns out, werewolves are as French as croissants and Chanel №5.

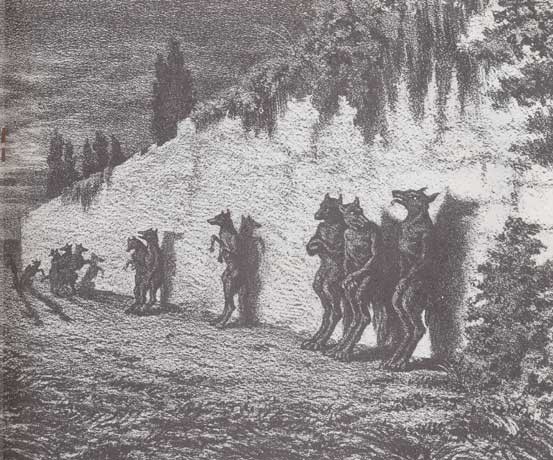

European concepts of the werewolf emerged from the warrior class of Germanic tribes, who revered the wolf as a potent symbol of hunter and fighter. Boys coming of age would symbolically become wolves through ritual.The French word for werewolf, loup garou, originally comes from the Norman Frankish tribal word werwolf, or “wolf man,” which filtered through Low Latin as gerulphus, which the French misheard as garez-vous, or “beware.” So loup garou can be translated both as “wolf to beware of” or the rather redundant “wolf-man-wolf.”

The concept really caught on in France. One of the first mentions of a werewolf in print was Marie de France’s poem “Bisclavret,” circa 1200. A Brittany baron, Bisclavret disappears for three days of every week. Eventually, he tells his wife he is transforming into a wolf, hiding his clothes so he can change back to human form. Horrified, the baroness has her husband’s clothes stolen, trapping him in wolf form, and she remarries. Her treachery is eventually uncovered, and Bisclavret regains human form — after tearing his ex-wife’s nose off.

With the rise of Christianity in the Middle Ages, Germanic pagan beliefs were suppressed and wolf-men became associated with the devil. Europe’s first witch trials were held in 1428 in Valais, a French-speaking area that’s now Switzerland. Alleged witches were accused of raiding cattle in werewolf form. Trials like these spread across Europe, peaking in the 1600s and dying out in the 1700s.

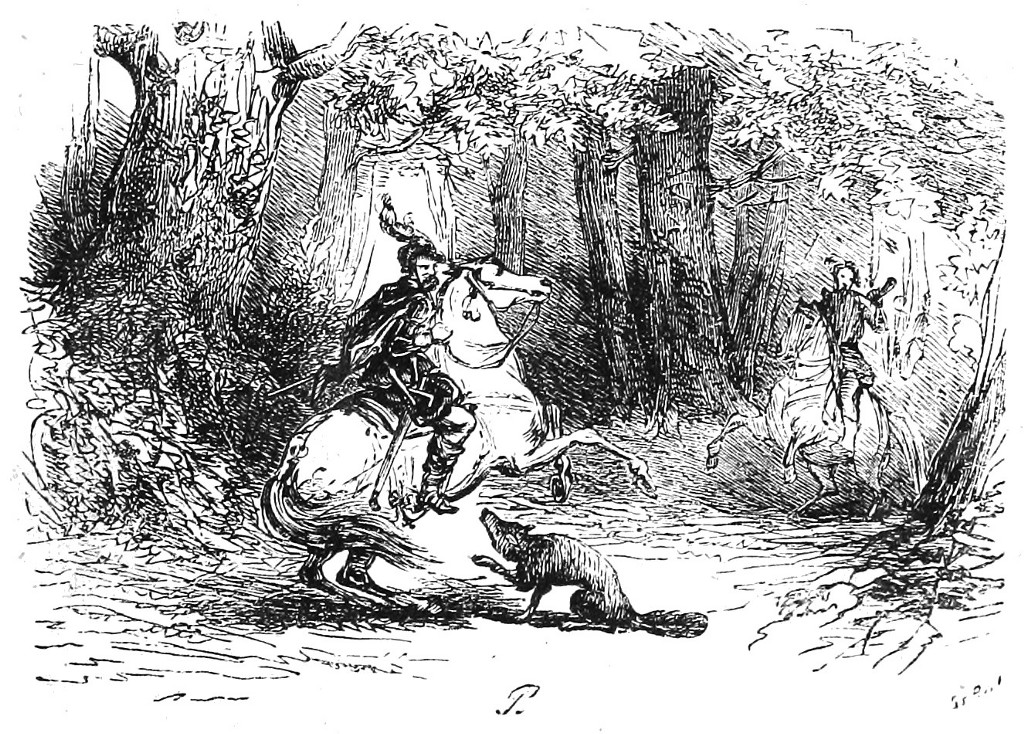

Just as the trials were dying out, people began dying in the rural Gévaudan region of southern France in 1764. Corpses were found horribly mutilated, their throats torn out. Survivors of attacks gave numerous, well-documented accounts of a ravenous wolf the size of a horse, with a terrible roar.

“All who have written to me regarding the size of this animal agree that it is larger than a wolf…some say it is a hyena, others a panther, still others a loup-cervier; this is all I know for certain about this terrible animal.”

—Local official M. de Lachadenède, Oct. 1764

Among panicked peasants, there was speculation the attacks were the work of a loup garou. Famed wolf hunters (yes, they had those) were called in, and thousands of people scoured the woods and valleys hunting for the “Beast of Gévaudan.” They killed more than 100 wolves, and thought they’d killed the beast on numerous occasions, but the attacks continued, claiming up to 113 lives over three years. French tradition credits local hunter Jean Chastel with killing the beast — writers spiced up the tale by saying he’d used a silver bullet.

Biologist Karl-Hans Taake, however, says the beast was probably killed by poison bait, which had been laid across much of the area. After a close review of the considerable historical record, Taake is also certain that the beast was no wolf, and certainly not a loup garou. In National Geographic, he writes that “There can be no reasonable doubt that the Beast was a lion, namely a subadult male.” Taake postulated it had escaped from a private menagerie.

When French settlers journeyed to the New World, they brought the loup garou with them.

“In French Canada, a man (always a man) becomes a loup-garou because of some punishment from heaven. One man, for instance, found that he was a loup-garou because he had not been to Mass (or confession) for ten years. Deliverance from the state of loup-garou comes by religious exorcism, by a blow to the head, or by the shedding of his blood while in the metamorphosed state.” — Maria Leach, Standard Dictionary of Folklore

To this day, French Canadians go on annual loup garou hunts. In Louisiana, Cajun parents warn their children that the loup garou, or hougarou, will eat them if they misbehave.

“In one way or another, everybody believes in it,” Barry J. Ancelet, professor of French at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette told the student newspaper of Nicholls State University. “Whether they believe seriously that there is a character who roams the night or not is unimportant. They believe in the stories…It becomes a way of connecting one generation to the next.”

In Canada, Haiti and Louisiana, a loup-garou doesn’t even have to be a wolf-man, but can transform into a horse, a pig or even a tree.

In Haiti, some versions of loup garou aren’t shapeshifters at all, but “once-human beasts whose souls have been devoured.” Anyone you know could be a loup garou, and the accusation was quickly levied against cheaters and deceivers, or just anyone who had had an unexpected stroke of good — or bad — fortune.

Still, at Halloween time, the image that persists in most of our minds is a towering wolf-man with huge claws and slavering jaws. And for that, like beef bourguignon and coq au vin, we largely have the French to thank.