This Guy Wants You To 3D Print Every Fish In The World

And you can do it for free.

Adam Summers is interested in fish. Like really interested. His e-mail address starts with “fishguy.” Pixar brought him in to make sure the animals in “Finding Nemo” were anatomically correct (they were, for the most part, but they had to remove the sexual organs from the sharks because they looked weird). And now he’s working on a project that could change the way scientists all over the world study them.

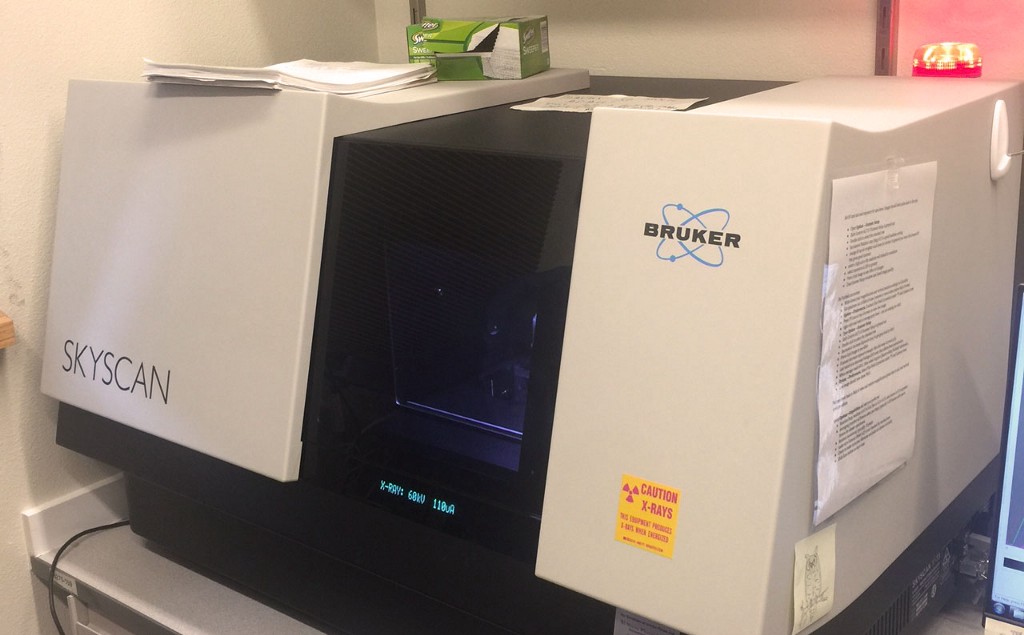

Off the coast of Washington State, about an hour north of Seattle, is a little island called San Juan. The University of Washington maintains a lab facility there. And in one of the buildings at that facility I meet Summers, who’s sitting in front of a $340,000 CT scanner with a cloth-wrapped “burrito” of five different fish inside.

The scanner is passing X-rays through the fish, slowly rotating it to capture a cross-section of each animal and saving those cross-sections to a computer. When it’s done, it’ll be able to squish all those individual images together and transform them into something really amazing.

The final product is an insanely detailed 3D model of each fish’s skeleton. The accuracy of the scanner is hard to believe — if you zoom in far enough, you can see individual imperfections on the scales. And you can view the skeletons from any angle, at any cross-section. He brings up a scan of a piranha and strips away the front of the head. I can see the row of teeth, with a second row of replacements forming in the jaw. It’s an unbelievable experience.

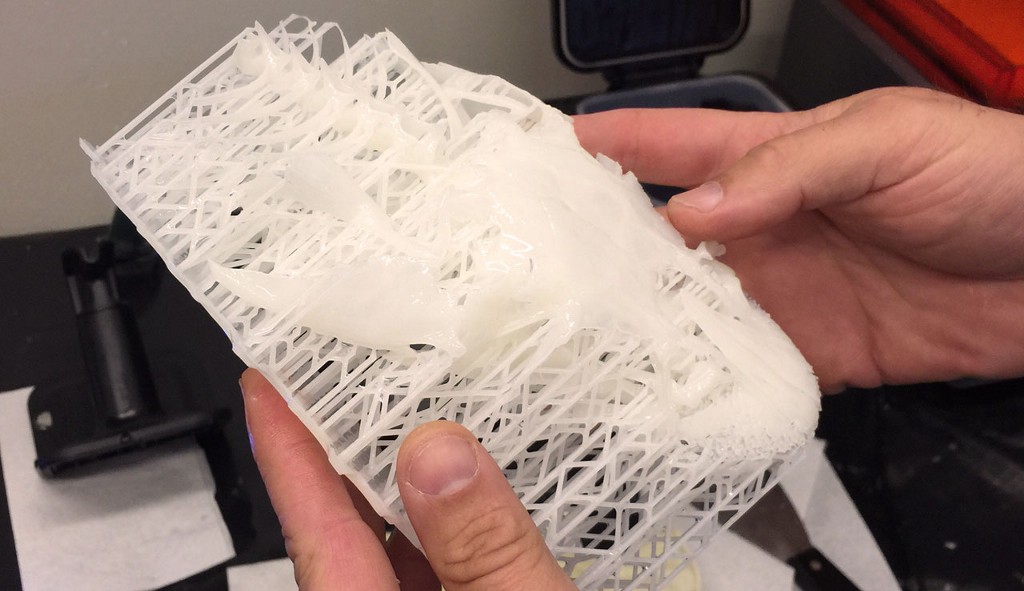

We then go over to another room, where Summers has a 3D printer. He’s just finished a model of a fish’s head and holds it up so I can see. The actual animal is about half the length of your pinky finger, but he’s blown it up so the head is as big as your fist. To be able to physically examine the specimen at that size gives you even more insight as to how its skeletal system functions.

Summers sets the model under a repurposed UV dryer from a nail salon to set and we go back to the scanner.

There are some 330,000 different species of ray-finned fish alone. That would take one scientist their whole career to scan, if they were lucky and also drank a lot of coffee. That’s where the second part of Summers’ plan comes in: it wouldn’t just be him doing the scans. He’s opened the labs to scientists from all over the world. You bring your specimens, he’ll book you a window of time and you can digitize them.

Anybody can use the scanner. Even non-scientist San Juan locals, if they want. Summers wants the machine to be running 24 hours a day, collecting data from as many fish (and other animals — a few people have brought geckos in already) as they can.

Here’s the cool part, though: if you scan, your data goes up on the Web for the whole world to see and use. Models are posted on the Open Science Framework and can be downloaded and explored by anyone.

Previously, to examine these skeletons would require a researcher to cut open the fish specimen, essentially destroying it. Now they can be studied over and over again from anywhere.

He tells me that it’s not just fish guys looking at these 3D models. People are using it to inspire artwork, like the video game developer who is taking players through virtual flythroughs of the skeletons. And because all of the software used for the project is free to use, anyone on Earth can get involved.

When I visited, Summers had a little over 700 species scanned, plus about 30 that were still unidentified. He was starting to ramp up after a slow June and July, with two visitors bringing suitcases of fish specimens this week. Timewise, there’s no end in sight for the project. His motto is simple: “Scan all the fishes.” And I’m pretty sure he’s going to do it.