People Used To Get Sloshed And Go Vote

Booze for ballots is a tradition as American—and as old—as George Washington.

Face it, America: We have atrocious voter turnout. In the last presidential election in 2012, it dropped to 57.5%. Never mind the midterms, which in 2014 attracted only 36.4%, the lowest since much of the country was away fighting World War II. While countries like Australia have mandatory voting, that’s seen as un-American. What used to be very American? Giving voters tons of alcohol to get out the vote on election days.

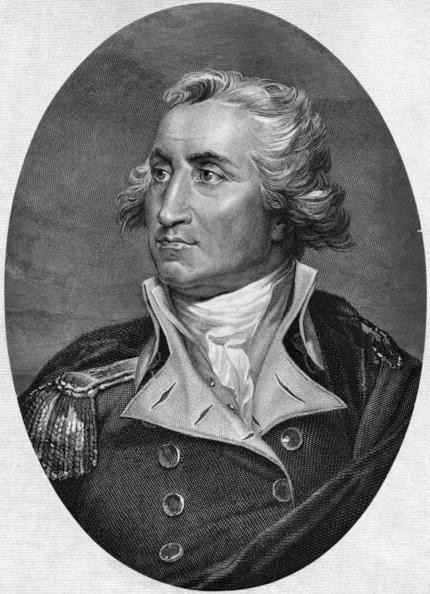

The tradition was already strong in Britain, and crossed the Atlantic to her colonies in America. When a 24-year-old George Washington lost a run for the Virginia legislature in 1755, author Daniel Okrent says he attributed the loss to not supplying sufficient alcohol to voters. By the time Washington ran again two years later, our future first president had learned his lesson. In “Drinking in America: Our Secret History,” Susan Cheever writes:

“He delivered 144 gallons of rum, punch, cider and wine to the polling places distributed by election volunteers who urged the voters to drink up. At 307 votes, he got a return on his investment of almost two votes per gallon.”

We must remember that voters back then had to trudge or ride to the polls, arriving tired and thirsty to what was an all-day affair. Colonists also drank about twice as much spirits as we do today. Because clean water was scarce and booze was often the only available medicine, they slurped the stuff from sunup to sundown. A colonist quoted in Colonial Williamsburg epitomized the Georgian attitude:

“If I take a settler after my coffee, a cooler at nine, a bracer at ten, a whetter at eleven and two or three stiffners during the forenoon, who has any right to complain?”

While election-day binges were de rigeur in Britain and America, they horrified foreigners like French traveler Ferdinand Bayard, whom Cheever quotes as saying, “Candidates offer drunkenness openly to anyone who is willing to give them his vote.”

Many Americans also looked askance at election-day booze-buying, known as “treating” or “swilling the planters with bumbo” (a drink of rum, sugar and nutmeg). Cheever quotes George Prentice, writing in the Louisville Journal of his horror at witnessing a three-day election-cum-party in Kentucky:

“During that period whiskey and apple toddy flow through our cities and villages like the Euphrates through ancient Babylon.”

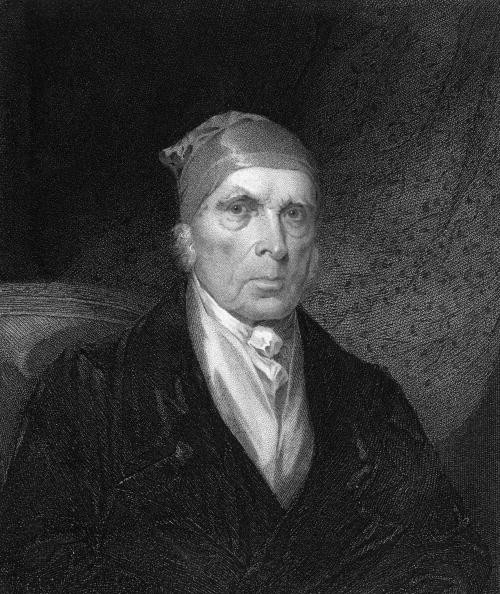

When future president James Madison ran for the Virginia assembly in 1777, he declared drinking on poll day “inconsistent with the purity of moral and republican virtues,” declined to serve alcohol, and lost. And in 1811, Maryland prohibited candidates from buying alcohol for voters.

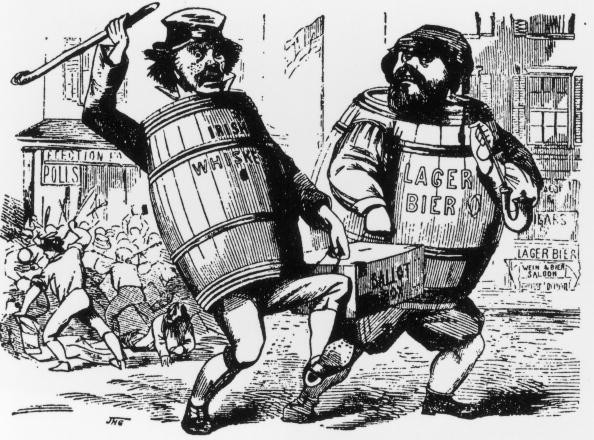

Still, for the next century, piss-ups at the polls remained widespread in America. The fact that many voters (and election officials) were sozzled certainly aided electoral fraud — as did the fact that polling places were often set up in saloons.

In a widespread practice known as “cooping,” people were seized, forced to drink and made to vote several times, receiving more drinks each time. Immigrants were frequent targets. (There’s also a theory that cooping led to poet Edgar Allan Poe’s death in 1849.)

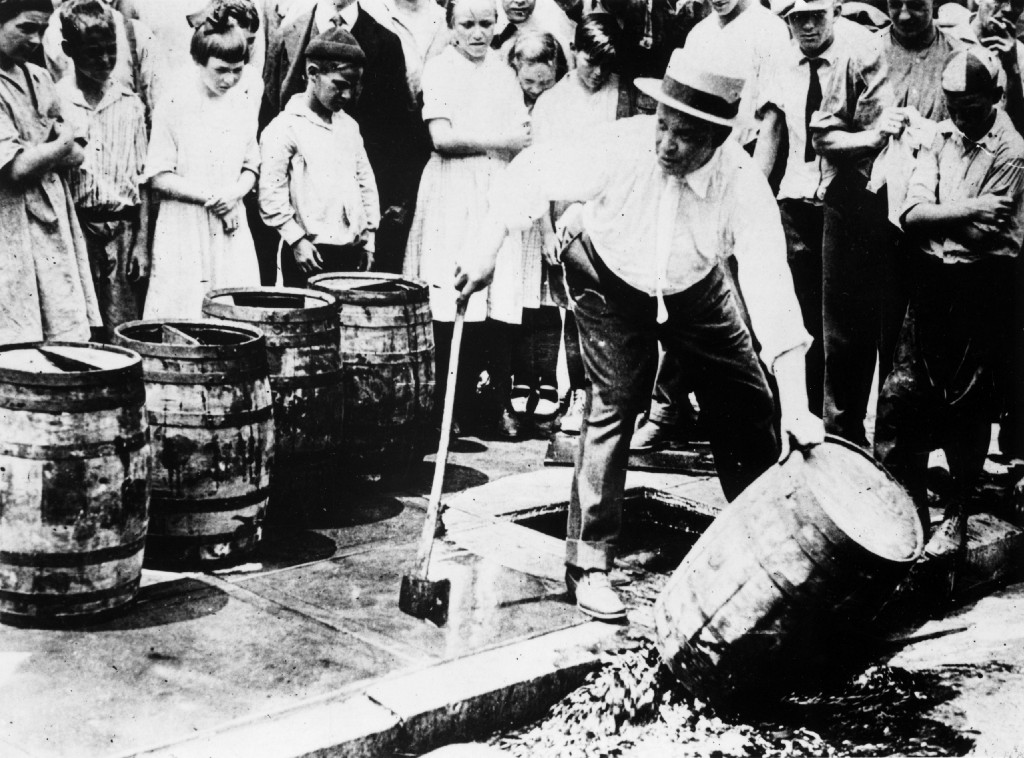

States began to ban drinking on election days in the late 19th century, but it was Prohibition that brought the party at the polls to a screeching halt. The temperance movement had zeroed in on election-day drinking as one of alcohol’s principal social ills, responsible for bribery, corruption and fraud. Drinking became illegal at the federal level in January 1920.

Prohibition changed American political culture for good. Yes, you can now buy booze on election day in every state but Alaska. Sure, most candidates will sip a pint to prove they’re cool. And yeah, campaigns still stock up on booze to celebrate their election-night victory (or defeat). But Election Day will never be the crazy, drunken national party it once was. And that’s a good thing…right?