Were Dolphins Really Caught Having A Human-Like Conversation?

Dolphins are amazing, but we’re not so sure about Dolphinese yet.

Headlines have been circulating about a group of Russian researchers who claim they recorded—for the first time ever—a pair of dolphins having a ‘human-like’ conversation. It’s no surprise several leading experts from around the world aren’t convinced by the research.

In fact, Richard Connor, a marine biologist who has been studying dolphin social interaction for more than 30 years, had a pretty strong dissenting opinion: “It is complete bull, and you can quote me,” he said.

Let’s look into it, shall we?

Problem 1: A poorly designed experiment

The first problem Marc Lammers—an expert on dolphin acoustics—notices is how the so-called conversation was recorded.

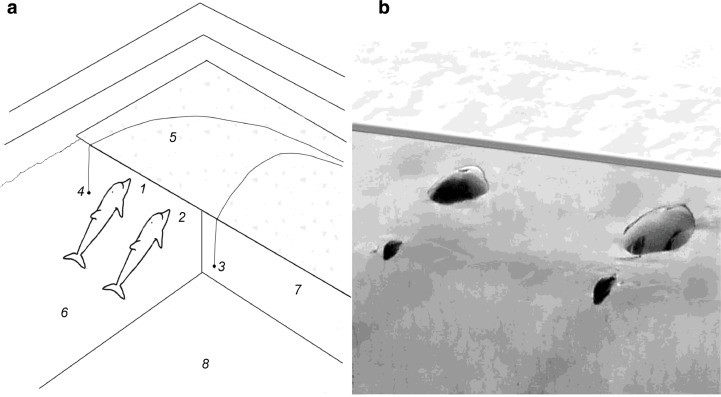

“Dolphin clicks are highly directional, with the energy focused in front of the animal, much like a flashlight,” he explained. In the Russian study, instead of recording the sounds at the hypothetical middle of the flashlight, the recording was made at a 90-degree angle—which would undoubtedly change the way the sounds were heard.

He explained how this type of recording would be somewhat equivalent to recording a conversation from the next room, while the people spoke into pillows—which sounds like a pretty terrible way to understand a conversation, as any good eavesdropper knows.

He was also bothered by the fact that the dolphins were recorded when their heads were at the surface of the tank—the place where air and water meet can cause strange reflections of sounds. Lammers said without applying counteractive measures, there is no good way to tell what sounds the dolphins actually made and what sounds were just reverberations of those sounds.

He said the paper “effectively ignores most of what is currently known about the properties of dolphin clicks” and suggests that instead, the researchers present “[their] own ideas for how dolphin communication might work by weaving together some simple observations with various disconnected notions of acoustics, cognition, and language research.”

Problem 2: Drastic Conclusions

Denise Herzing, research director of the Wild Dolphin Project, also points out that the conclusions made in this paper make some jumps without any real facts to back them up.

She has been studying dolphin communication for more than 30 years and said while we do know dolphins are capable of understanding spoken and gestured language (like in training at SeaWorld, for example), there is no reason to believe they communicate in the same conversational way humans do when they’re in the wild.

She also had to refute one of the most sensationalized findings stating the dolphins didn’t interrupt each other before speaking, which the Russian researchers interpreted as meaning they were listening to each other and considering a response before delivering it. Herzing said this discovery is old news and it’s been established dolphins communicate without overlap since 1979.

In the end, leading scientists are casting a doubtful eye on the research that’s been reported on from outlets ranging from The Huffington Post to Jezebel—which is another point of contention for many of these researchers who have spent decades working for this kind of breakthrough.

“The biggest problem,” said Connor, “is that now when people make real scientific discoveries on dolphin communication, the public, having been exposed to this nonsense, will not be impressed because they will think Russian researchers already showed that they have language.”