One Of The Convicts Who Escaped Alcatraz In 1962 May Have Surfaced

by hunter_stuart, 7 years ago |

7 min read

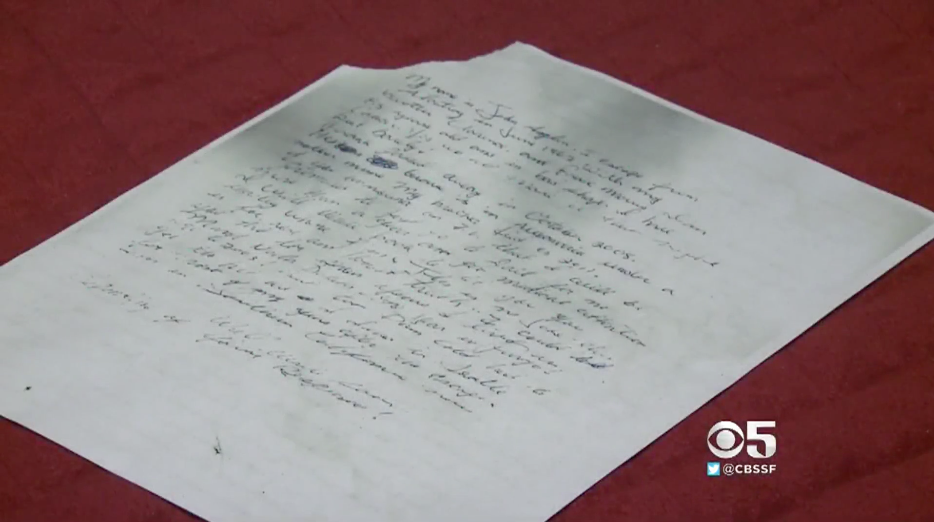

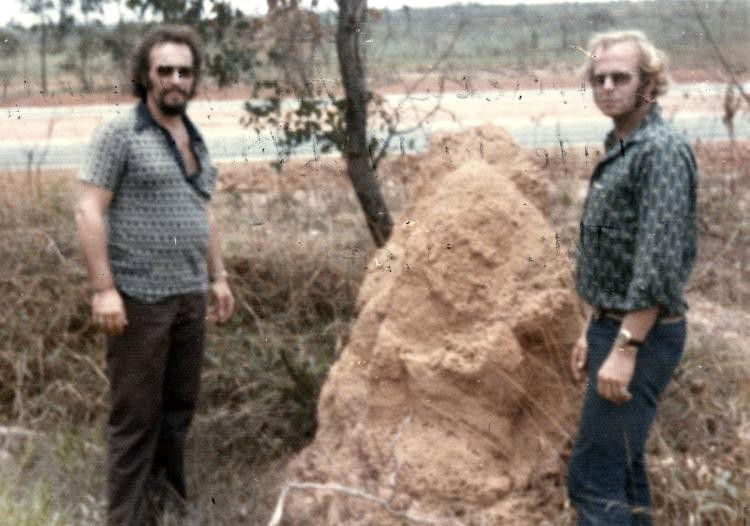

‘Yes, we all made it that night, but barely!’

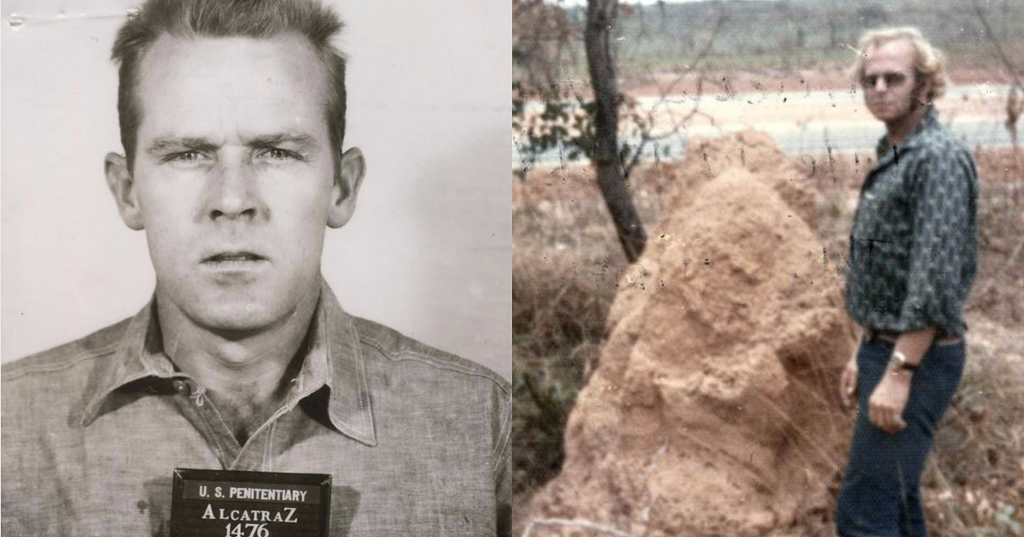

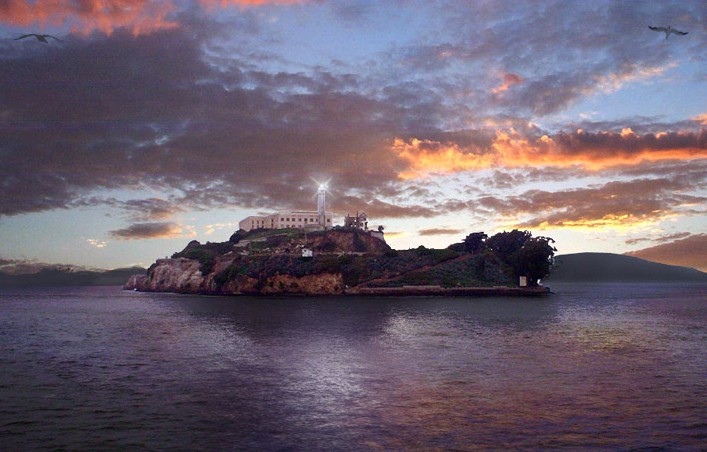

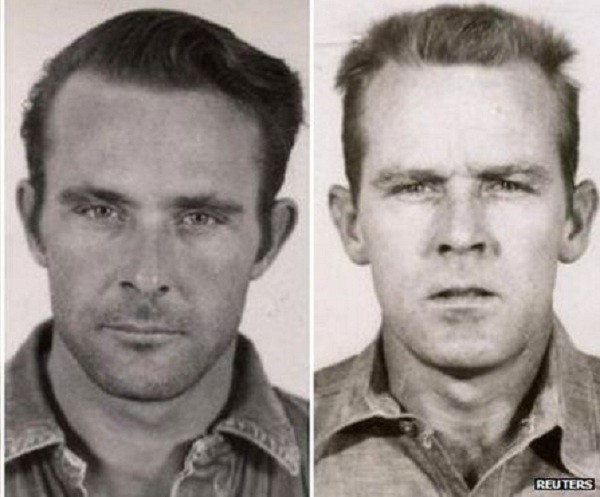

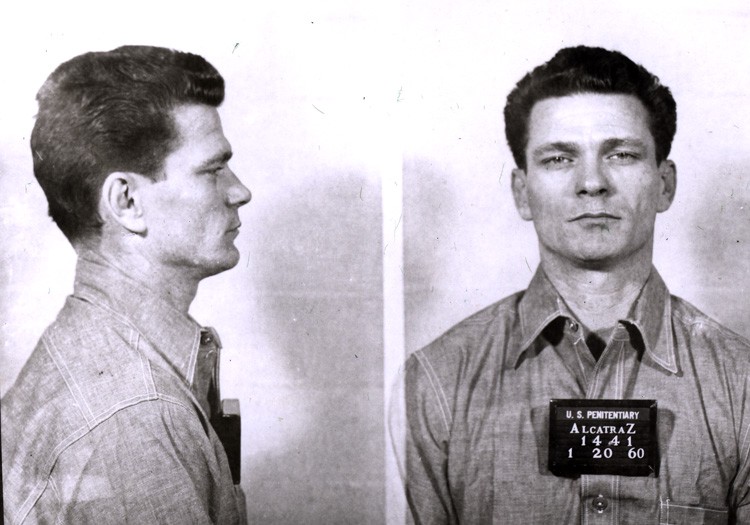

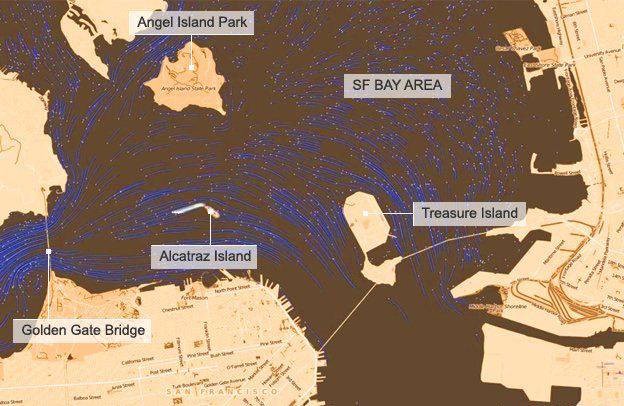

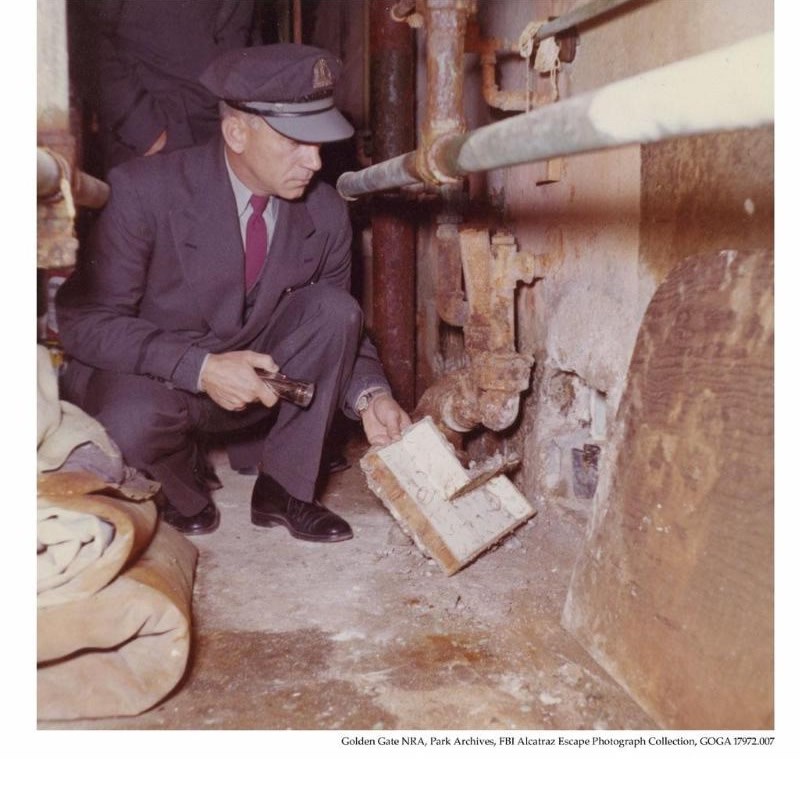

A new piece of evidence in the longest manhunt in American history surfaced last week, taking the public back into one of the most incredible fugitive stories of all time. On Jan. 22, CBS San Francisco obtained a letter allegedly written by John Anglin, the convict who escaped from Alcatraz in 1962 with his brother, Clarence, and another prisoner named Frank Morris. The three men are the only people in history who escaped from Alcatraz and are still unaccounted for, the U.S. Marshal for the Northern District of California, Donald O’Keefe, told OMGFacts through a spokesperson.

✕

Do not show me this again