The Real Story Of The Miracle of Dunkirk

The events behind the new blockbuster will blow your mind.

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight.

Military retreats are rarely considered to be victories. But when you save 340,000 people from getting strafed by Nazi Messerschmitt 109s and dive-bombing Stukas in the nick of time, well, yes — that’s a major fucking victory, okay?

That’s what happened at Dunkirk — a small town on the northern coast of France — in the early stages of World War II, before the US had entered the war.

The year before the evacuation was a relatively peaceful time. It was so devoid of action that people even called it “the Phoney War.” Little did they know what they were in for.

In the spring of 1940, the Nazis invaded Belgium, Luxembourg and Holland, totally catching the Allies off guard. The British had no choice but to retreat or be surrounded (and surely massacred) by the enemy. British commander Lord John Gort decided evacuation was the only chance for Britain’s survival.

It was a huge risk that ultimately helped decide the outcome of the war.

The evacuation of 338,000 British, French and Belgian soldiers from France back to England began on May 27, 1940 and lasted for eight horrifying days. At least 900 warships, fishing boats and pleasure ships (famously known as the “Little Ships”) sailed to the soldier’s rescue and brought them across the North Sea to safety.

The British government ended up asking anyone who had a boat to help, and hundreds of ordinary people heeded its call. The courage of those people became known as the “Dunkirk Spirit,” a nationalistic term that fueled Britain’s morale during the war and beyond.

Since the British saved more than ten times as many men as they expected to, the operation became known as “The Miracle of Dunkirk.” (It’s also sometimes called “Operation Dynamo,” because hey, why not?)

Today that spirit lives on in “Dunkirk,” a new movie directed by the British screenwriter Christopher Nolan, who is perhaps best known for writing “Inception,” “Memento” and several of the Batman movies including “The Dark Knight Rises,” “Batman Begins.”)

“Dunkirk,” which hit theaters July 20, tells the story of the miracle wartime operation in a kind of triptych of land, air and sea. Here too, is a triptych of unsung heroes who courageously contributed to the Miracle of Dunkirk.

On Land: Brigadier Edward Lawson

Edward Lawson grew up in England, the son of a colonel in the British Army. As a young man, he worked as a journalist in Paris and New York for his family’s newspaper. He served in both World Wars.

When the British Army entered France in 1940 in an attempt to stop the Nazis, Lawson was with them, commanding the 48th Division (an infantry force).

Things didn’t go so well: the Germans advanced into France a few months later, quickly making gains on the Allies. Lawson’s higher-ups in the British Army ordered him to create a line of defense along a canal in northeastern France in a last ditch attempt to stop the Nazi advance.

This would have been just fine — if the Belgian army hadn’t surrendered, leaving Lawson and his men vulnerable to attack. Lawson needed all the men he could get to hold his position at the canal; he scrounged up a makeshift army from demoralized British troops who were in the process of transiting to Dunkirk to be evacuated.

Lawson’s patchwork crew was absolutely vital. Why? Because if the Germans broke through his stronghold, it would be fatal for the thousands of British troops waiting on the beaches of Dunkirk just beyond.

And Lawson wasn’t going to let that happen.

He and his poorly equipped men kept the Germans at bay for a whole day while the British evacuated hundreds of soldiers from Dunkirk.

Lawson and his men were evacuated the next day. The British Army later awarded him for his heroism by giving him a prestigious decoration known as “The Most Honourable Order of the Bath.”

In the Air: Adolph “Sailor” Malan

South African-born Adolph “Sailor” Malan was a gutsy power player of the skies. Around 1925, he became a naval cadet before making the move to join Britain’s Royal Air Force a decade later — hence his nickname “Sailor.”

What Malan didn’t possess in skill, he made up for in courage. He was an expert tactician, ditching outdated strategies in favor of new flight formations. Those who knew him said he could take a damn good shot.

During the Miracle of Dunkirk, the Royal Air Force fought to shield its vulnerable soldiers from the bloodthirsty Luftwaffe. During the air battle, Malan racked up at least five kills, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross — a Royal Air Force award for “acts of valor, courage or devotion to duty”— in the process.

A few weeks after protecting the Dunkirk evacuation, Malan led the № 74 Squadron — one of the best units in the Royal Air Force — through the Battle of Britain, a grueling three-month air battle during which the Royal Air Force successfully kept the German Luftwaffe from bombing the UK to smithereens.

So, yeah — dude was a total legend. After the war, he returned to South Africa to fight against the government’s attempts to take away voting rights from people of color.

Sadly, he died of Parkinson’s in 1963 at the age of 52.

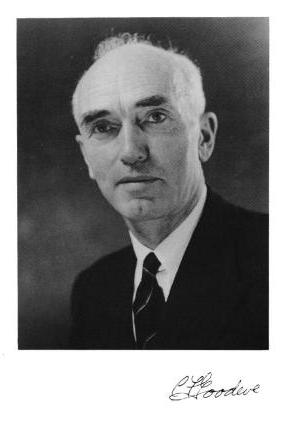

In the Sea: Sir Charles Goodeve

Sir Charles Goodeve, a Canadian chemist, believed science would help Britain’s war effort — and his crucial contributions to Operation Dynamo proved him right.

Goodeve was born in 1904 and moved to England in 1927 to become a research fellow, but as the Nazis began gaining power, he joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve and began studying naval mines.

During World War II, the Germans planted hundreds of naval mines in the ocean in order to blow up Allied boats and submarines. About half a million such mines were laid during the war, so they were a serious danger to the Allies, who desperately wanted to find a way to avoid them.

Goodeve helped them do that. The Germans had laid magnetic mines, which the War Is Boring blog explains well: “Steel warships create an invisible magnetic signature as they sail. Magnetic mines detonate when they detect this signature, even when they’re moored tens of meters [dozens of feet] underwater.”

Goodeve developed a technique called the “Double L Sweep” to disable these treacherous underwater bombs. The technique used two boats, a cable and a magnetic field to confuse the Germans’ magnetic mines.

This kept three vital British evacuation routes clear, allowing the British to complete Operation Dynamo without having all their ships blown up in the process.

Next, Goodeve discovered a process to protect a ship’s body from mines. He wiped ships of magnetic fields using an electrical cable with a current of 200 amps on the ship’s sides. It was like coiling, but cheaper and easier. He called it “degaussing” after the “gauss,” a unit measuring magnetic fields named after the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss.

In days, the British degaussed hundreds of ships, making them safe to sail over magnetic mines en route to the soldiers at Dunkirk. Goodeve was knighted and awarded the US Medal of Freedom for his impact on the mission’s success.

The evacuation of Dunkirk was messy, confusing and a great loss — 68,000 British soldiers were either captured, wounded or killed outright, while the Germans managed to capture another 40,000 French soldiers.

But if these 340,000 troops weren’t saved by the brains and bravery of people like these guys, the outcome of World War II could’ve been nightmarishly different.

As the New York Times put it at the time: “So long as the English tongue survives, the word Dunkirk will be spoken with reverence.”