The First Woman To Interview A President Got Him In The Nude

by k._thor_jensen, 8 years ago |

4 min read

Fake news? No, real nudes.

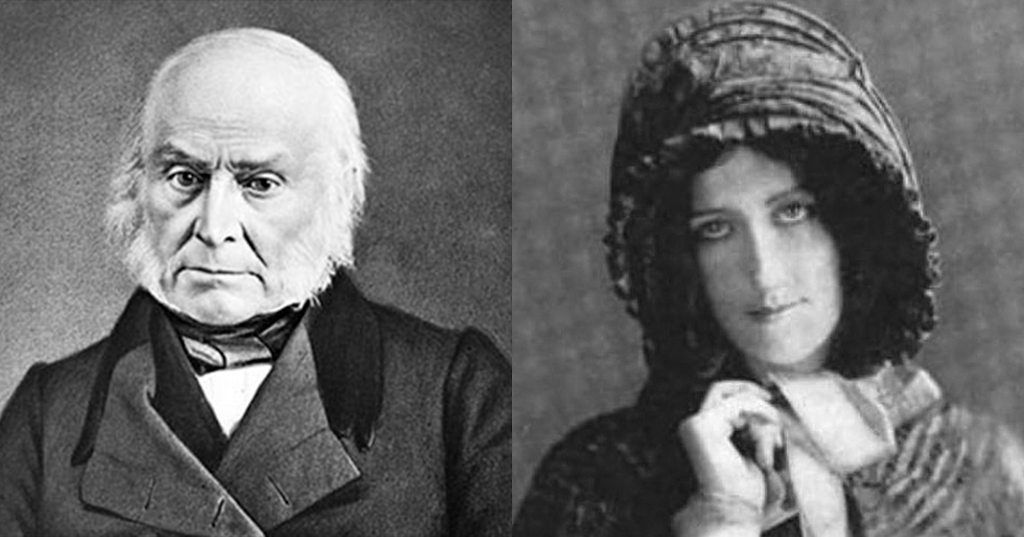

Donald Trump’s relationship with the media could best be described as strained. But that’s not a new thing for the Presidency. Since the founding of our nation, the Commander in Chief has jousted with the press. George Washington hated the partisan press of his day so much that he cancelled all of his newspaper subscriptions when he took office. In the 1840s, James K. Polk was infuriated when the papers pushed back on the war with Mexico. And we all know how a pair of curious reporters with an inside source brought down Richard Nixon. So Presidents are justifiably careful about who they talk to. Access to a solo interview with the most powerful man in the country is a badge of honor for a journalist, proof that they are to be taken seriously. But when Anne Newport Royall tried to meet with John Quincy Adams and become the first newspaperwoman to ever interview a sitting President, she had to do something not quite so serious. Royall was raised in a log cabin in western Pennsylvania and endured hardships that made her a fierce competitor with a thirst for justice. When her husband Major William Royall passed away in 1813, she sold off his land and used the money to travel the country.

✕

Do not show me this again