Before There Were Vibrators, There Were Sewing Machines

Getting off by stitching socks.

Tss-tss-tss-tss…tss-tss-tss-tss…tss-tss-tss-tss…

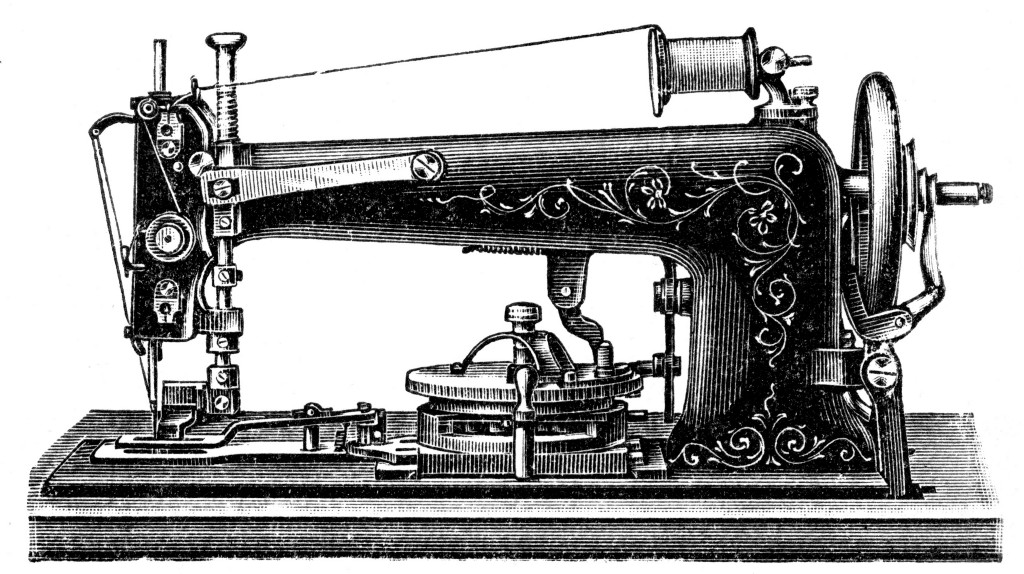

The gentle rhythm of a sewing machine can be meditative and masturbatory — at least according to 19th century physicians. You heard right: the dusty Singer your granny used to mend your sweaters was once considered a libidinous threat to a woman’s purity.

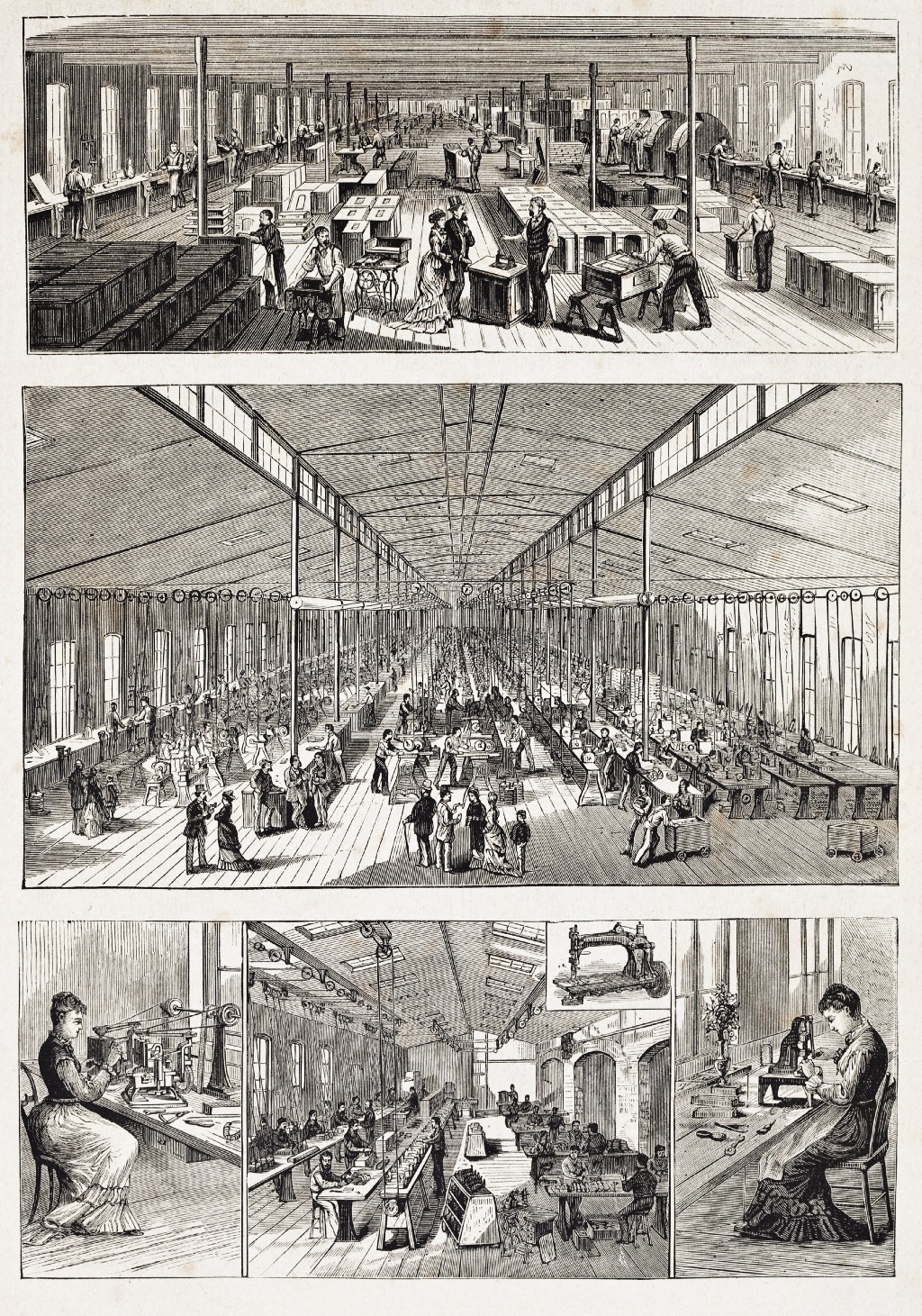

After Elias Howe invented in the sewing machine in 1846, the tool quickly revolutionized women’s lives and the entire garment industry. No longer beholden to hand stitching, seamstresses in newly minted factories made fast work of once tedious assignments.

On one hand, this was great — for the first time, women were empowered to leave home, join the workforce, earn money and operate machinery. On the other hand, they worked in dark, poorly ventilated factories where owners exploited their labor and pushed their bodies to the brink.

Thomas Hood’s 1843 poem “Song of the Shirt” (which reads like a rough draft of Rihanna’s “Work”) details the unpleasant life of an Industrial Revolution-era garment worker:

Work — work — work,

Till the brain begins to swim;

Work — work — work,

Till the eyes are heavy and dim!

Seam, and gusset, and band,

Band, and gusset, and seam,

Till over the buttons I fall asleep,

And sew them on in a dream!

If the long hours and terrible wages weren’t enough to drain the women (and children) who worked in these factories, the physical toll of operating the machines surely did. Women were required to sit on uncomfortable stools and power machines by pumping their foot on the treadle. Employees reported experiencing extreme fatigue, back pain and even hemorrhages.

Instead of attributing these ailments to rapid production pace, long hours or poor air quality, the (mostly male) doctors agreed that the problem was — wait for it — masturbation. According to The Fiber Archive, “In the 1860s, a small but impassioned debate broke out in both England, France, and the U.S. regarding the potentially ‘exciting’ effects of the sewing machine.” Physicians speculated that female garment workers intentionally pumped their thighs in a rhythmic motion to elicit a vibration from the sewing machine and stimulate their lady bits.

Dr. Langdon Down, best known for his work on Down syndrome, observed that women using a treadle (especially the sexy French double treadle!) were left with a “diminished luster” due to “increased blood flow” to the nether regions. Dr. Charles Malchow believed the friction of a sewing machine— much like that caused by riding a horse or a bicycle — could cause seamstresses to achieve orgasm at work.

In the 19th century, it was not uncommon for doctors to diagnose women with hysteria when they complained of any form of discomfort, sexual frustration or unhappiness. Doctors would prescribe vibrators or offer “hands-on assistance” (i.e. hand jobs) for sexual relief.

Physicians working directly for the textile industry were less sexually open-minded. At a time when “excessive stimulation” was a common diagnosis for any number of ailments, Dr. Eugene Guibout suggested that vibrating sewing machines not only threatened women’s physical health, they also endangered their moral health by encouraging impure habits.

Looking back, it’s far more likely that women suffering from “diminished luster” were not sex-obsessed but merely overworked. Rather than helping them by offering proper healthcare and improved working conditions, doctors shamed them and employers deprived them of pleasure.

The jury’s still out on whether or not anyone actually managed to climax from pedal pushing. But, truthfully, I hope they did — these women worked thankless jobs that endangered both their physical and mental health. If nothing else, they deserved a bit of under-the-table relief.