This Woman Made Doctors Believe She Gave Birth To Rabbits

And also cats and eels. Yup. EELS.

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight.

In September 1726, a poor, illiterate woman named Mary Toft gave birth to rabbits.

Mary lived with her husband Joshua in Godalming, a village outside London. At age 23, she’d already given birth to three children, one of whom died in infancy. During her fourth pregnancy, Mary miscarried.

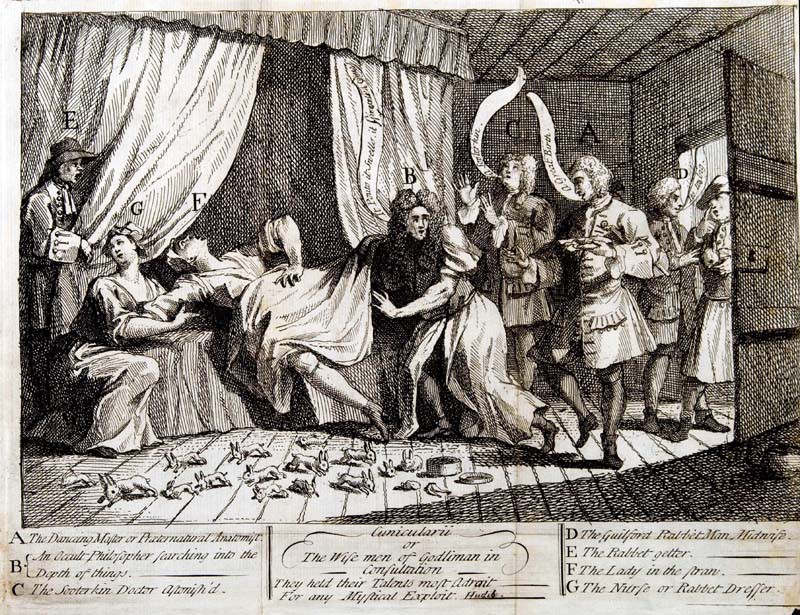

A few months after her miscarriage, a doctor was summoned to Mary’s bedside. He found her in the midst of a most unusual labor during which she expelled a rabbit’s head and foot from her birth canal. But things didn’t stop there: Over the course of the next several days, Mary delivered an assortment of animal parts from cats, rabbits and eels, as well as a litter of nine whole, stillborn baby rabbits.

Even in Georgian England, news of a woman birthing bunnies travels fast. Doctors intent on witnessing this medical miracle (or was it a freakshow?) hurried to her bedside. It wasn’t long before Mary’s story reached King George I, who quickly dispatched his personal doctor to investigate.

By the time Nathaniel St. Andre, Surgeon and Anatomist to the Royal Household, reached Mary, she’d birthed 15 rabbits. St. Andre did a cursory examination on her and promptly insisted she be brought to London for a closer look. St. Andre later published his findings in a pamphlet titled “A Short Narrative Of An Extraordinary Delivery of Rabbets.”

In late November 1726, just a few months after the first rabbit made its appearance, Mary was moved to a public bath in London. (Back in the day, women would sometimes stay in bathhouses after giving birth to let their bodies heal — they were kind of like makeshift hospitals.)

In completely related news, sales of rabbit meat in England plummeted around this time.

The hoax, explained

It should have been blatantly obvious to the many doctors who attended her that Mary was not giving birth to small woodland creatures. In fact, she was taking pieces of chopped-up rabbits and ramming them up her hoo-ha, where they remained for several hours before being unceremoniously ejected during one of her many faked labors.

According to Mary, the hoax began during her last pregnancy — the one that resulted in a miscarriage — when she saw a rabbit in a field. The rabbit sighting triggered weeks of cravings that she could not accommodate, as her family was too poor to afford rabbit meat.

Mary wasn’t alone in perpetrating the hoax: Her husband, sister-in-law and mother-in-law, who happened to be a midwife, “helped” her out. Mary was also aided by the condition of her body — many of the doctors who examined her mistook her post-miscarriage state for an active pregnancy.

Like most poorly thought-out schemes, Mary and her family got into the rabbit-delivering game in hopes of making a quick buck. Human curiosities were big business in England at the time and the Toft family thought people might pay to see a pregnant woman give birth to Peter Cottontail.

Another theory holds that Mary’s family may have dreamed up the whole hoax and coerced her into participating. Karen Harvey, a professor of cultural history at the University of Sheffield, says Mary may have felt pressured to go along with the scheme because of her inability to produce human children. See, as a woman, her primary job was to give birth to a lot of children who might grow up to help the family earn money. When she was unable to do that, the family might have forced her to use her body for a more devious purpose.

Harvey also floats the idea that Mary’s rabbits may have been a form of political protest against landowners. Thanks in part to the Agricultural Revolution, small rural areas like Godalming, where Mary and Joshua lived, were rapidly declining. For Mary and her family, the rabbits may have seemed like an easy prank to play on a group of upper-class elitists: At the time of Mary’s prank, wealthy landowners in the region were buying up large plots of once-communal land and calling them their own. The practice was called “enclosure” and it was a major source of frustration for poor farmers like the Tofts. Mary’s prank hasn’t been directly linked to enclosure, but if the Tofts’ rabbit prank was a form of political protest, it’s likely the indignities they suffered because of enclosure motivated them to fuck with their rural overlords.

“I shall sooner hang myself”

After her transfer to London, it was only a matter of time before Mary’s plan began to fall apart. The London doctors were not as easy to deceive as Nathaniel St. Andre. After they threatened her with invasive surgery, Mary confessed. “I will not go on any longer with this. I shall sooner hang myself,” she said.

Mary spent several months in a prison in Westminster. But since she’d committed no crime, the criminal proceedings fizzled. When Mary died in 1763, the parish register recorded her death with the words “Mary Toft, Widow, the Impostress Rabbitt.”

Mary Toft’s hare-brained scheme was highly unpopular among both doctors and rabbits of the time. We may never know for sure who initiated the prank or why Mary and her family made the choices they did. Still, the creativity, commitment and sheer audacity required to pull off the stunt make the Toft family — and Mary in particular — heroes of the highest degree.