This Athlete Broke The Color Barrier 50 Years Before Jackie Robinson

by ilana_gordon, 8 years ago |

5 min read

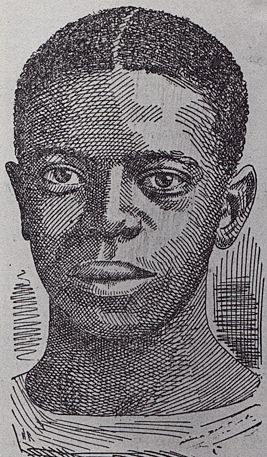

They called him ‘The Black Cyclone.’

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight. Before basketball, there was track cycling. Invented in the mid-1800s, track cycling was briefly the №1 spectator sport in the US. Initially designed to test athletes’ endurance, the sport was exciting, exhausting and impressively dangerous. Bicycles were invented in the early 1800s, but early designs overlooked a few key features (think: the ability to steer; brakes). It wasn’t until 1885 when the Rover Safety Bicycle was released that cycling experienced a surge in popularity. As biking became a cultural phenomenon, track cycling emerged as a challenging sport for athletes and a new entertainment option for viewers.

The birth of the “Black Cyclone”

Breaking the color barrier

Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947 when he signed on to play second base for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Major Taylor broke cycling’s color barrier 50 years earlier when he began racing professionally. In 1896, Major moved from Indianapolis to Worcester, MA to get serious about cycling. At 18 years old, he competed in his first major race at Madison Square Garden and took eighth place. From there, Major’s cycling career accelerated and in the next three years, he broke seven world records and won a national championship and an international championship. Major’s years of athletic dominance were marred by racism. Riders colluded to eliminate him from competition by pushing him off the cycling track. Spectators dumped ice water on him as he rode and placed tacks in front of his bicycle wheels to slow him down. Athletes and fans threatened him and judges refused to acknowledge his victories. At the turn of the century, Major was one of the highest-paid athletes in the world. He brought in about $10,000 a year (equivalent to $275,000 today). Despite his wealth and success, he was regularly refused service by hotels and restaurantsSpinning his wheels

Major Taylor remembered

Sixteen years after his death, Major got the memorial he truly deserved. A group of retired cyclists and Frank Schwinn of Schwinn Bicycles collaborated to give Major a proper funeral. They paid to have his body exhumed and moved from the welfare section of Mount Glenwood Cemetery in Cook County, Illinois to a more respectable part of the graveyard. Today, Major’s influence is felt throughout the cycling world. In 1982, the Major Taylor Velodrome opened in Indianapolis; the cycling team at Indiana University is named in his honor. In Worcester, he is regarded as a hometown hero. Major’s contributions to track cycling are unassailable, but his name is not synonymous with racial progress the same way Jackie Robinson’s is. This can only be attributed to track cycling’s fall from grace — the buzz surrounding this exhausting, thrilling sport fizzled around World War II. As basketball, football and baseball rose in prominence, track cycling — and Major Taylor — were left in the dust.✕

Do not show me this again