Meet Virginia Oldoini, The OG Kim Kardashian

She wrote a book titled ‘The Most Beautiful Woman of the Century.’ It was an autobiography.

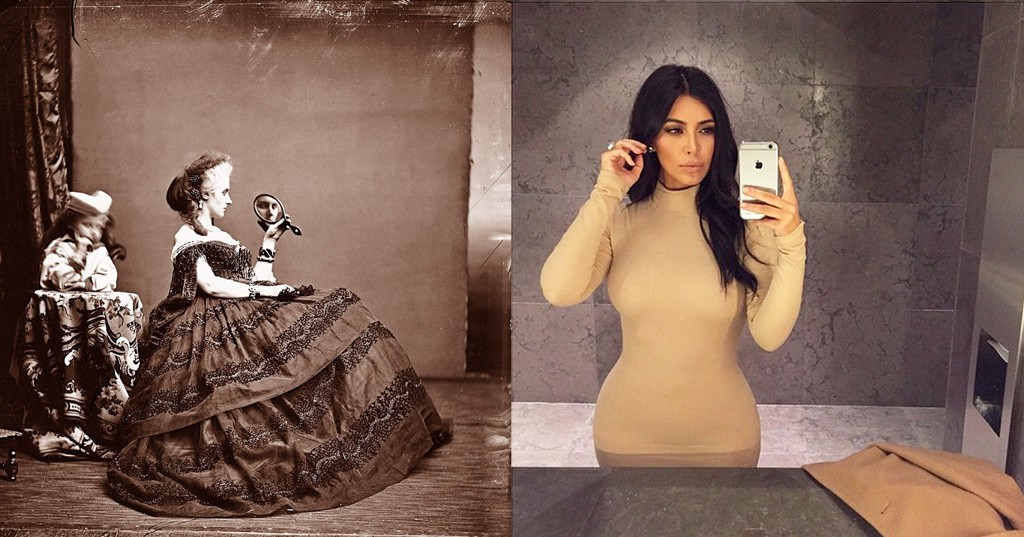

What does the world’s most (in)famous reality TV star have in common with an early 19th century Italian countess? Besides a ton of money, haters and controversy — the title of “Selfie Queen.”

Virginia Oldoini was born in 1837 to a venerable Florentine family. At 17, she was married off to Count di Castiglione. It didn’t work out. Two years and one child later she had shamelessly cheated and bankrupted him, then promptly set off for Paris. There, she had a short-lived affair with Napoleon III that solidified her reputation as an extravagantly popular, incomparably beautiful and unabashedly vain woman. Think “It Girl” meets “Femme Fatale.”

So arrogant was the Countess de Castiglione that she once made an entrance to a ball draped on the emperor’s arm dressed as the Queen of Hearts. “The heart is a bit low, Madame,” the empress famously mocked. At gatherings the Countess refused to speak to women, “would appear like a goddess descended from the clouds, and allow people to admire her as if she were a shrine.” Perhaps most tellingly, she began writing a self-retrospective titled “The Most Beautiful Woman of the Century.” She wouldn’t live to finish it.

But we may not have known about (and certainly wouldn’t have cared enough to discuss at length) the Countess de Castiglione if it weren’t for her lifelong relationship with the camera. Over the course of a relatively short life, the Countess had over 400 photographs taken of herself by Pierre-Louis Pierson. Rather than be a passive subject, the Countess acted as art director for her selfies, choosing her costumes, poses, camera angles and what we’d now call “post-production processes.” She was no stranger to taking paintbrush to image to transform and embellish. In other words, she was the original Selfie Queen.

In La Divine Comtesse, a book of photographs of the Countess, the curator Pierre Apraxine notes how the Countess’ body of work has long been thought to be trivial and narcissistic. Apraxine acknowledges that the Countess predated the Surrealism movement attributed to artists like Cindy Sherman and Claude Cahun. Despite this, Broadly’s Rosalind Jana points out that “Apraxine cautions against viewing the Countess’ work as feminist.”

This is where I would have to disagree and call upon another, more contemporary Selfie Queen, whose name has been dragged as a narcissist throughout her career — as though appreciating yourself makes you some kind of vapid egomaniac.

Her name is Kim Kardashian.

After the debut of Kardashian’s book “Selfish” in 2015 (a book composed entirely of selfies), Leah Bourne of StyleCaster said Kardashian had “ushered in a new kind of fame, one in which you can be famous for seemingly being nothing more than yourself.”

Considering that, it seems to me that Countess de Castiglione predated Kim by about 150 years.

Perhaps the Countess and Kim offer the world nothing but a vapid assemblage of self-worship. Or maybe — even if only subconsciously — each produced a covertly feminist work of art, acts of reclamation by the world’s most talked about and photographed women, respectively.

The Countess’ early photographs drew on characters from mythology, Biblical symbolism, literature. She is Queen Anne Boleyn, Queen Eritrea, a corpse, a nun. Her favorite prop is a mirror.

Through these photographs the Countess documented her life’s triumphs. Her Queen of Hearts costume, her son Giorgio. She plays dress-up, she spins tales. At one point, she sent a terrifying image to her ex-husband when he attempted to take Giorgio away. It was titled “Vengeance.” In it, she stands staring in a rather murderous way, a knife in her hand dripping fake blood. (The Count got the message. Giorgio remained in his mother’s custody.)

To call her merely a “raging narcissist” seems unfair at best, irreverent at worst.

Kim’s “Selfish” documents a span of time — it’s a progression from childhood to megastar, featuring cameos from friends, siblings and business associates. It allows us a glimpse into her life, despite the fact that even her “unflattering” photos smack of self-service (she’s funny! She’s relatable!)

The Countess’ progression is different. It’s raw and disturbing, in images cataloguing mental deterioration and instability.

One could almost feel the Countess’ grief over her loss of youth through photographs. Disconnection is a big theme: One image is dominated by her bare bloated feet. In another, half her face is masked by an oval picture frame, an eye peering directly through as though to preemptively judge us before we have an opportunity to do so first. As Sarah Boxer puts it in the New York Times, “Prettiness was not the point. By this time, she knew she was falling apart.”

By this time — meaning 1870 — the Countess disappeared from society. She kept no mirrors in her house, the walls of which were painted black. She only stepped outside while veiled and under the cover of darkness.

Whether a lifetime of unparalleled vanity or a sick mind were responsible for the Countess’ unwillingness to accept time’s steadfast march is impossible to say. We know that for 25 years she hardly left her house and when she did, it was to document her own disintegration. Like I said — tragic.

If this seems like a defense of the selfie, it is. Can you blame a girl for wanting to be remembered on her own terms?

As though cause for pity, Boxer writes: “The Countess was desperate to know what it must be like for others to behold her.”

Aren’t we all?