The First Computer Programmer Was This 19th-Century Noblewoman

Ada Lovelace put the ‘count’ in ‘Countess.’

Our Unsung Heroes series brings history’s unknown badasses out of the footnotes and into the spotlight.

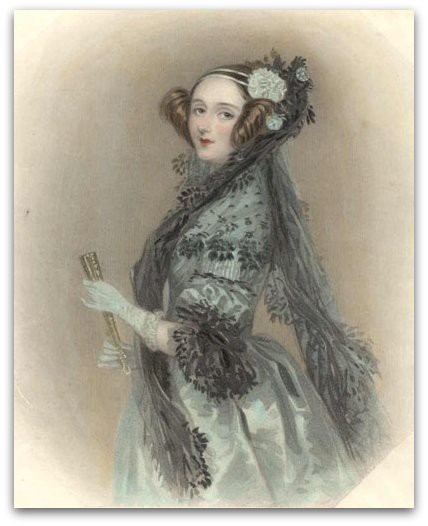

It’s hard to escape legend with a name like Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace. Luckily Ada, the founder of scientific computing, not disappoint.

Ada Lovelace was born on December 10th, 1815. She was the reason for and result of a very brief marriage between famous poet Lord George Byron and Lady Anne Isabella Milbanke Byron. The couple separated weeks after Ada was born. While the separation had much to do with Lord Byron’s drinking and debt, the affair he had with his half sister certainly didn’t help. Motivated by disgrace, Lord Byron exiled himself from England and never saw Ada again. He died when she was only 8.

Bye, Byron. Hello, Mathematics.

In an attempt to discourage Ada from following in her father’s artistic footsteps, Lady Byron insisted she be taught science, language and mathematics. Such studies were absolutely unheard of for young girls, but Ada had a natural aptitude for the subjects. However, her mother’s hopes of squashing Ada’s innate fantastical tendencies backfired. Ada became enamored with the idea of flight and began studying birds. At the age of 13, she designed the concept for a flying machine.

At 17, Ada was officially considered a woman and began attending parties. Naturally, she used this opportunity to find hotties.

Whoops! Nope, sorry. Other scientists. She used this opportunity to find other scientists. In 1833, she met Charles Babbage (or, as we know him, “The Father of The Computer”) at a party and their intense conversation on math turned into an even more intense letter correspondence spanning seventeen years. Nerd genius recognized nerd genius. He became a mentor to her and she was greatly influenced by his concept for the Difference Engine. Described by Betsy Morais as “a tower of numbered wheels that could make reliable calculations with the turn of a handle,” I imagine it must have looked like a room-size steampunk calculator.

When Charles Babbage went on to create a more advanced Analytical Engine, Ada was the key interpreter. She translated a scientific essay about the machine written by mathematician Luigi Federico Menabrea. As she translated from French, she decided to add a few notes of her own. By the time Ada was finished, the essay had more than tripled in size. Mannnnn, the woman was non-stop. If you’re feeling nasty, you can read the whole essay here.

If you ain’t feeling nasty at the moment, here’s a little snack to awaken your hunger.

“A new, a vast, and a powerful language is developed for the future use of analysis, in which to wield its truths so that these may become of more speedy and accurate practical application for the purposes of mankind than the means hitherto in our possession have rendered possible. Thus not only the mental and the material, but the theoretical and the practical in the mathematical world, are brought into more intimate and effective connexion with each other. We are not aware of its being on record that anything partaking in the nature of what is so well designated the Analytical Engine has been hitherto proposed, or even thought of, as a practical possibility, any more than the idea of a thinking or of a reasoning machine.”

In this essay, Ada not only predicted the application of computers to areas beyond mathematics, she also PROPHESIED the modern computer. When the essay was published in a scientific journal, her contribution was credited with only her initials. Because it’s hard out there for a woman.

In 1852, Ada’s health deteriorated as she suffered from uterine cancer. Her husband and children were there for her as her condition worsened. Oh, and Charles Dickens was there, too. The novelist read to Ada on her deathbed.

Ada died in November 1852. The year of her death, the most noteworthy inventions were clothespins and potato chips. The founder of scientific computing barely lived long enough to be graced by the invention of cutting and then heating a potato.

Like most great stories, though, Ada’s doesn’t end at her death. 2009 saw the inaugural celebration of international Ada Lovelace Day, a holiday now celebrated every second Tuesday in October. This year, there were over 80 events spanning six continents to celebrate Ada and her accomplishments. It’s been over a century and a half since Ada’s death, and her example continues to inspire. Oh, and she happened to be pretty right about computers, too.